Retiring Boomers are going rural (but not too rural)

There is a lot of buzz amongst urbanists and demographers about the increasing gravitation of young adults towards urban areas. We’ve found evidence to support this narrative in some areas of Virginia, including indications that they may be staying even after having kids.

But there’s also a lot of talk about baby boomers retiring and moving into cities. Maybe this is happening in other parts of the U.S., but it’s certainly not the case in Virginia.

On the contrary, they appear to be heading for the hills. In fact, despite Forbes Magazine naming Virginia its 5th best state to retire in, Virginia does not appear to attract many retirees in general.

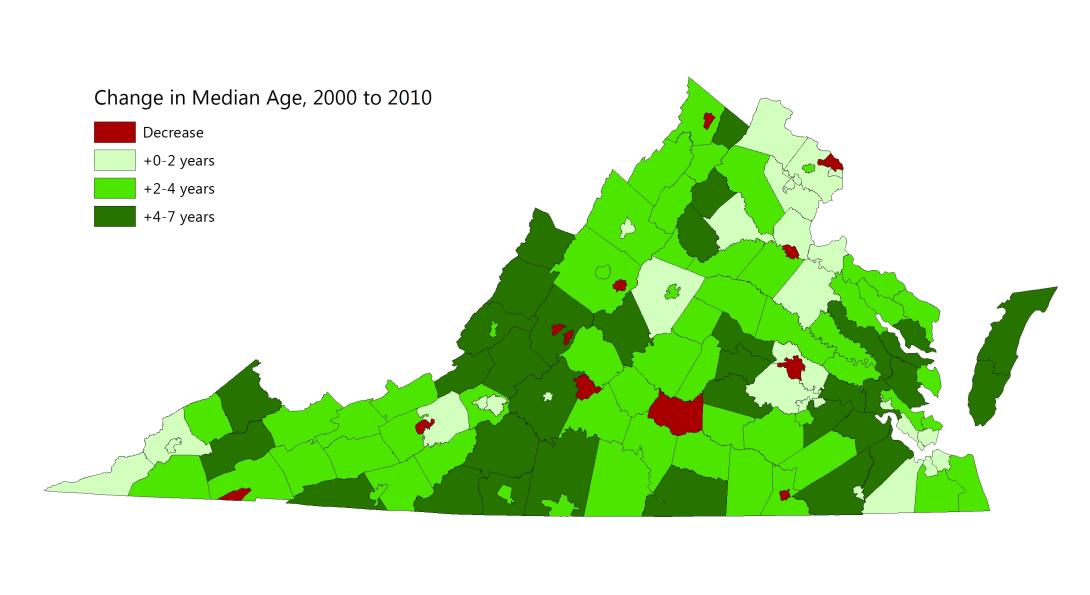

Virginia is aging quickly, as can be seen on the map below. From 2000 to 2010, the median age in the Commonwealth rose from 35.7 to 37.5. In some localities, it rose by as many as 5 or 6 years in just that 10-year period. But most of that is due to a gradual decline in birthrates, not older people moving in. From 2000 to 2010, migration accounted for only a slight (1-2%) increase in the population of age groups around retirement age, and that increase was smaller than the state’s overall growth rate.

Migration of Retiring Baby Boomers

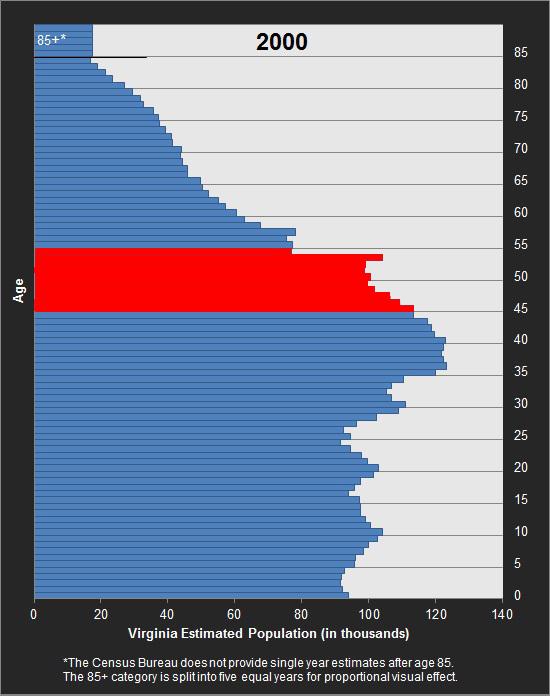

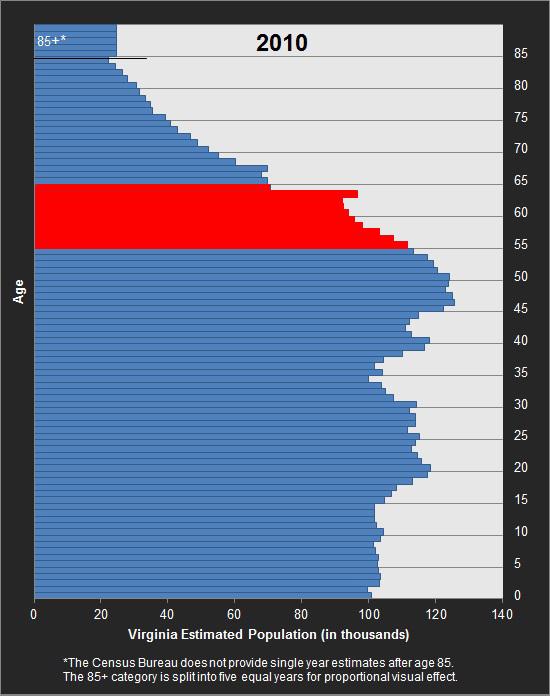

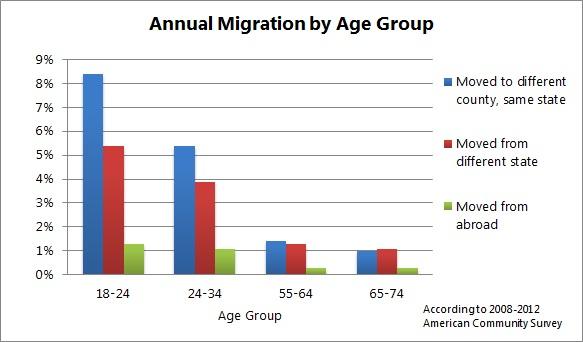

Members of the leading wave of baby boomers, born after the end of World War II in 1945, are currently about 68. In 2010, when the last census took place, they were right at 64. To figure out where they’re starting to retire, I looked at where they moved between the 2000 and 2010 censuses. The group I am primarily looking at was born between 1946 and 1955. They were 45-54 during the 2000 census and 55-64 during the 2010 census. Here’s what they look like in relation to other groups:

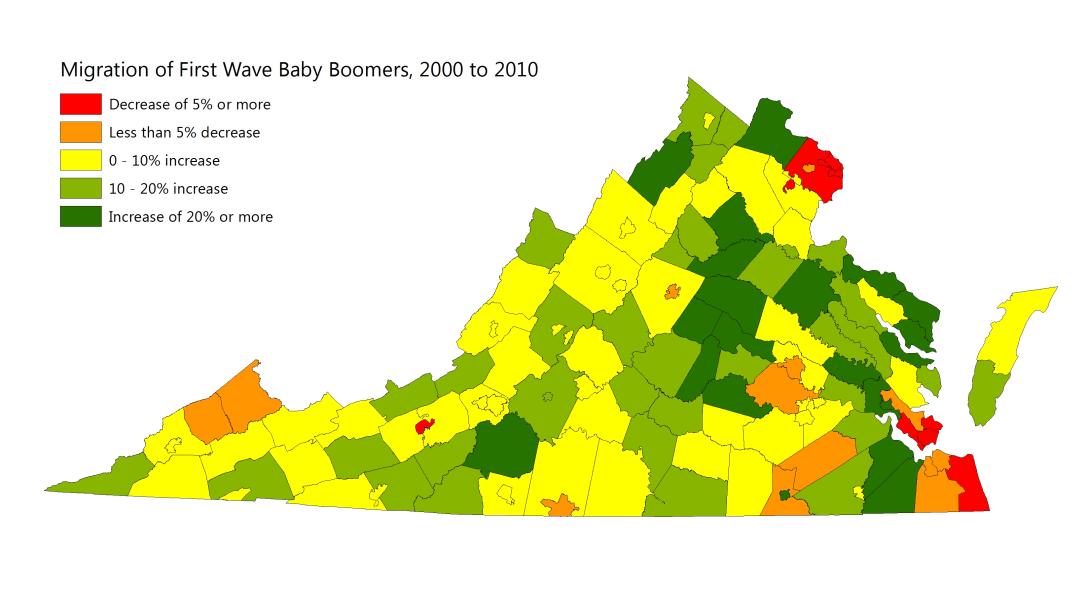

In order to tease out the net gain or loss from migration, I used locality death records from the Virginia Department of Health to subtract deaths from the population, then looked at what changes existed after that.

Aging vs Migration

Baby boomers make up, as their name implies, a significantly larger generation than the generations preceding them (see the graph above). That means that, even in localities that baby boomers are abandoning, their presence is still notable. The locality will feel like there are more older people, because there are.

Take the City of Manassas for example. In 2000, there were 4,589 people aged 45-54 (born between 1946-1955). Using VDH records, I estimated that 206 of them died over the next ten years. That means we would expect there to be 4,383 people aged 55-64 in the 2010 census. However, there were only 3,648 of them, a loss of 16% of the population in that age group.

Yet the number of people in the 55-64 age group grew from 2,220 in 2000 (6.3% of the population) to 3,468 in 2010 (9.6%) – a huge rise. This rise doesn’t mean retirees are moving to Manassas (they’re leaving in droves), rather the sheer number of people in the baby boomer generation means there will be more retirees and elderly people everywhere.

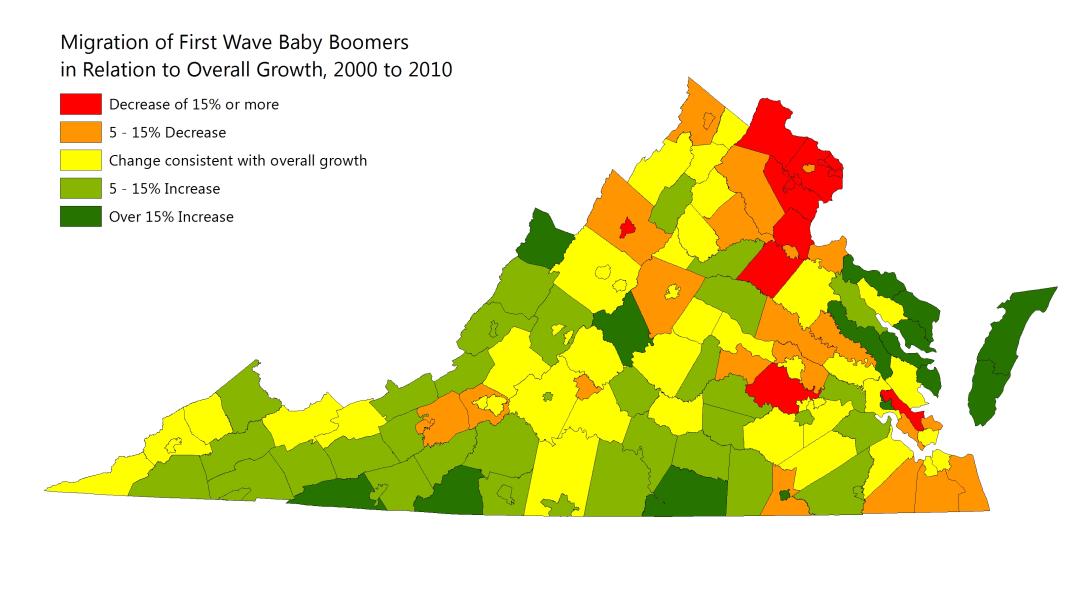

Here’s where retiring Boomers are migrating:

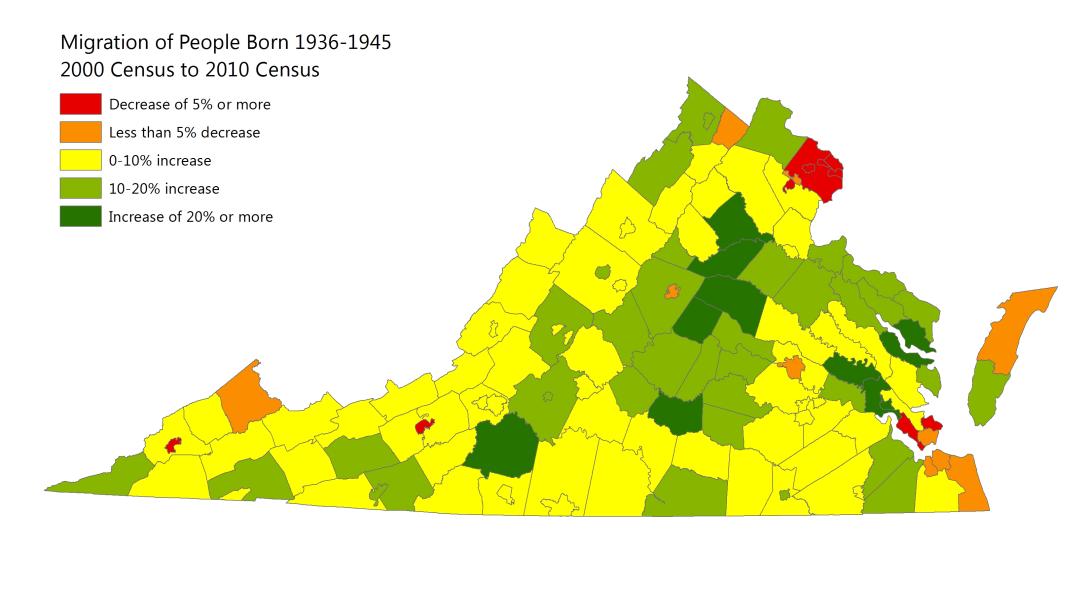

I also compared them to the group ten years older – those aged 55-64 in 2000 and 65-74 in 2010 (born 1936-1945). The two groups’ migration patterns were remarkably similar.

Here is the migration of baby boomers relative to the growth of the locality as a whole. There are a few localities for which this number is important. For instance, Loudoun County had 25% more first-wave baby boomers in 2010 as in 2000. But it’s overall population nearly doubled in that time, so the population of retirees grew much more slowly than the population of other groups.

A few takeaways from these maps:

1. Retirees are not big on cities or suburbs. They are especially eager to get out of Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads. Smaller cities seem to have more stable numbers, but are still mostly net losers.

2. They’re not exactly flocking to distant rural areas either, however. The most popular localities for retirees seem to be beautiful rural land within an hour or two of a major metro area. Some big retirement destinations include the Eastern Shore and Tidewater peninsulas, the central Piedmont (Orange, Fluvanna, Louisa, Goochland), the Blue Ridge counties (esp Franklin, Bedford, and Nelson), the 460 corridor, and Bath and Highland Counties. More isolated parts of Southwest and Southside Virginia are less popular.

3. Percentages obscure the population disparities. As you can tell from the map, many localities are seeing sharp increases in the number of retirees, while only a few are seeing decreases. But the localities losing retirees are some of the largest in the state. Fairfax alone lost over 20,000 retiring baby boomers. That’s about a 13% decrease for Fairfax, but enough to account for dozens of other counties’ gains.

4. Older people are not quite as mobile as younger people. While there are certainly localities that are losing retirees and localities that are attracting them, the numbers aren’t as extreme as they are for younger people. A healthy majority of the population seems to stay put throughout the early retirement years. This makes sense, since younger people report moving much more often than older people.

Why is this important?

As we have pointed out before, there are quite a few counties in Virginia that are rapidly losing their young people (or have low birthrates). However, many of them continue to appear to be growing due to aging or in-migration of retirees. These counties may face a different situation than they are accustomed to. The elderly are less dependent on commute times to work and can help maintain property values in declining rural areas. They also come without kids, meaning school enrollment declines – and property taxes with it. Several counties may arguably be turning into “school tax havens” for people who don’t have kids and don’t want to pay for other peoples’. Retirees can be an economic boon for service jobs in areas that are economically distressed, but they are also unlikely to start businesses or bring new industries.

Localities will have to plan for the future based on these trends and planners will probably have to adjust their expectations and rhetoric about urban retirees.