Virginia is getting older

Like many people, I’ve been inclined to explain Virginia’s decades of explosive population growth in terms of migration and the Federal government’s expansion in Northern Virginia. While that’s certainly part of the equation, “natural increase” has actually driven most of the growth, just as it has across the country. Natural increase simply means more people are born than die in a year. Even in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, natural increase is the largest generator of population growth. But “natural increase” does not mean that we are having lots and lots of babies. In fact, it has much more to do with the fact that we had a lot of babies a while back and since then people started living a lot longer.

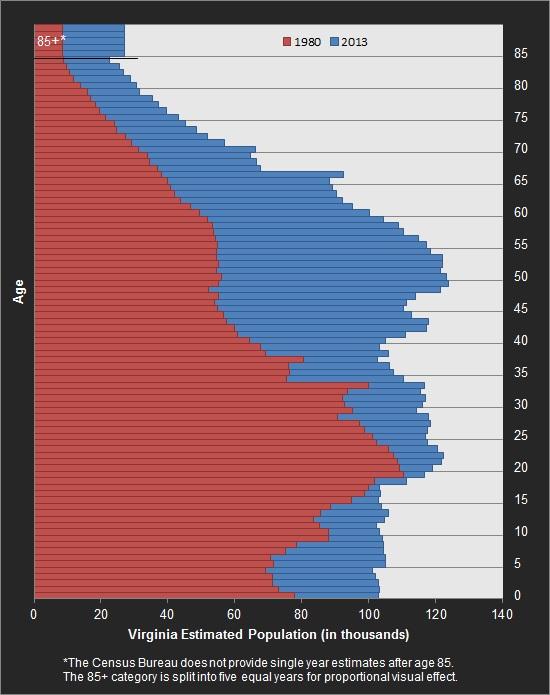

You hear, on this blog and elsewhere, about the “aging population,” but I wanted to show exactly what that means. Here’s the one gif you need to see to understand population growth in Virginia:

A few quick observations:

Census Estimates

These graphs are based on the Census Bureau’s intercensal estimates, produced annually and based on a formula that ages people and moves them around between actual counts. This formula has been tweaked over the years (you may spot a significant correction to it after the 2000 census), but is generally accurate. The most accurate graphs here are those immediately after actual censuses (1980, 1990, 2000, 2010).

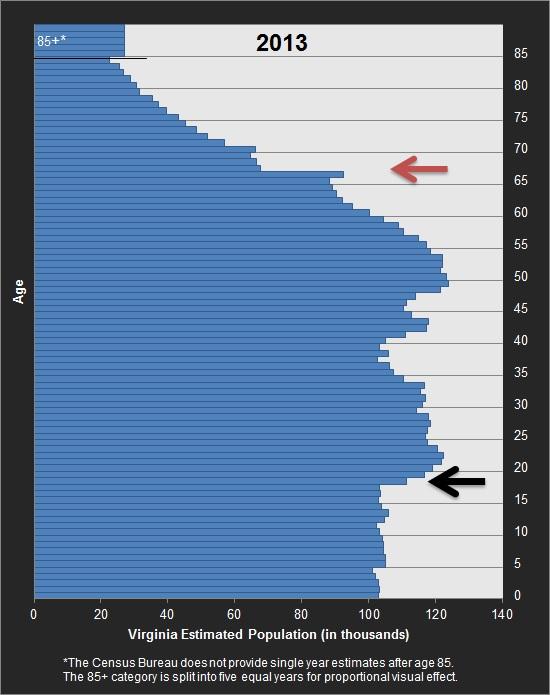

The College and Military Bump

Virginia almost always gets a little bump around age 19 from an influx of students at its top-notch colleges and enlistees at its many military bases. It’s not big enough to overshadow larger generational trends, but it’s definitely visible. While some of those people end up leaving four or five years later, quite a few end up sticking around.

The Baby Boomers

Here’s the 1980 graph superimposed on the 2013 graph. It’s easy to see where the big gains are coming from.

The appropriately named “baby boomers” have transformed the country at each stage of their development. They’re now poised to transform it again as they retire. In addition to simply being a larger cohort than previous generations, they are also looking at a much longer life expectancy. They will make huge demands on social security, the medical system, and pension programs that were designed for earlier eras of shorter lifespans and fewer elderly. The Virginia Retirement System, Virginia’s public employee pension program, was changed significantly in 2012 to try to cope with the expected shortfall.

Additionally, for all the talk of how milennials are changing growth patterns in urban areas, baby boomers may have an even larger impact. With retirement looming, many have started moving out to rural counties. In numerous rural counties in Virginia, the population should be falling due to the loss of young people, but doesn’t because older residents arrive to take their place.

The first wave of baby boomers is now somewhere around the age of 68 (red arrow), so strap yourself in for a wild retirement system ride over the next decades. Coincidentally (actually not a coincidence at all), World War II ended about 68 years ago, flooding the United States with returning soldiers.

Other Than the Millennials, Later Generations Just Aren’t As Big

Part of the reason milennials are having such a big impact is that there are quite a few of them. The college and military boost makes it almost as big as the baby boomer generation in Virginia. Like every generation before them, they have flocked to cities. Meanwhile, there haven’t been nearly as many people in the prime of their suburban-home-buying 30’s. Historic patterns of suburbanization may revive once milennials get a little older and have more kids, but then again, maybe they’ll decide they like it where they are (or can’t afford to leave) now that their kids are in school.

But the generation after the milennials is not nearly as big. The first wave of that smaller generation is just now reaching 18 to 19 years of age (black arrow). The first institutions to feel the impact of this shift may be colleges, who have already reported lower numbers of applications. Several large schools had planned to expand and have been unable to do so, while smaller schools have felt the pinch as there are fewer applicants to go around.

The Low-Fertility Trap

Complicating all of this is the low birthrate for women who are in what statisticians traditionally consider prime childbearing years. We keep waiting for the big boom in births from the large cohort of women in their late 20’s and 30’s, and it has simply failed to materialize. With smaller cohorts now entering those prime childbearing years, we could be looking at the beginnings of a cycle of population reduction with long-reaching implications.