Rural Virginia: Death in paradise

Most of Dickenson County‘s residents live along the many river valleys that flow down into the Russell Fork which cuts through Virginia’s Cumberland Mountains to create the largest gorge east of the Mississippi. Yet despite its many scenic attractions and the bonus of a low cost of living, Dickenson has been steadily shedding its population, declining by over a third since 1950.

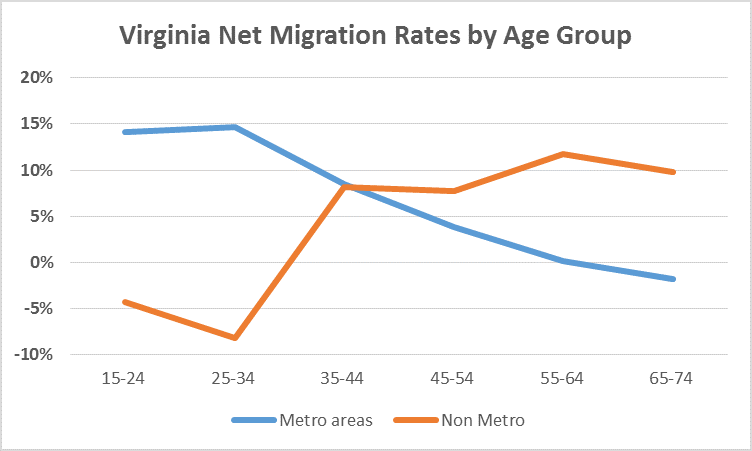

Rural counties in Virginia, like Dickenson, have been slowly losing their young adult population for decades as many have moved elsewhere to seek more education and work opportunities. But often rural counties have been able to continue growing by attracting older migrants who are nearing retirement or have already established their careers elsewhere. However, these two migration trends are now creating a new problem for most of Virginia’s counties; the gradual hollowing out of their young adult populations from decades of out-migration combined with a growing retiree age population means that in an increasing number of counties, there are no longer enough families with children to replace the rising number of deaths.

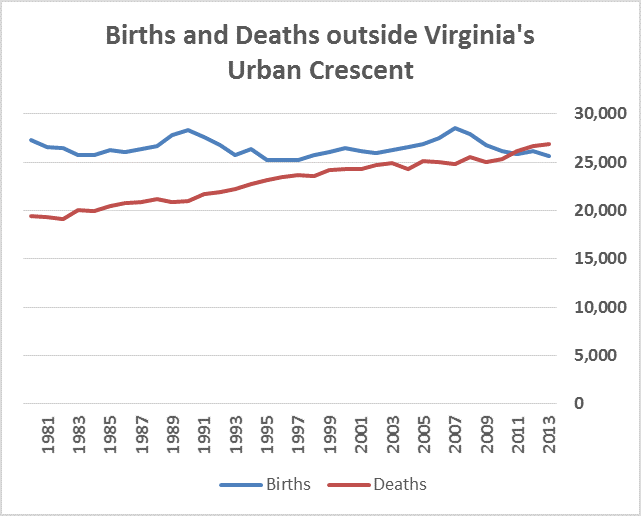

In 1980 only a handful of rural counties on the Chesapeake Bay and several Independent Cities had more deaths than births (natural decrease). Since then natural decrease has spread and is occurring in surprising places. Goochland County with its horse farms, golf courses and subdivisions is hard to confuse with Dickenson County. Yet, Goochland has also begun to have more deaths than births due to its young adults moving out and retirees moving in. In 2013, localities outside of Virginia’s Urban Crescent, which stretches from Northern Virginia through Richmond to Hampton Roads, accounted for a quarter of the Commonwealth’s births but nearly half of its deaths.

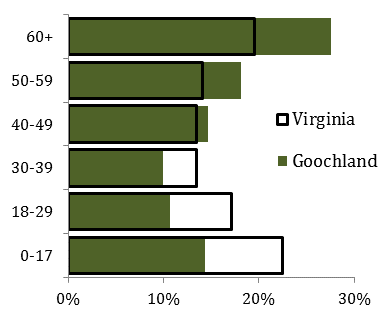

Since its population began experiencing natural decrease in recent years, Goochland, like Dickenson, has also begun to decline in size, after growing by nearly 30 percent just a decade ago. The aging of both counties’ populations played a large role in causing natural decrease. In 1980, the median age in Goochland County was 32, but by 2014 its median age was 47. Today, Goochland has twice as many residents over 60 years old as those under 18 years old, and twice as many residents in their 50s than in their 20s.

Though few counties see a shrinking population as desirable, natural decrease typically makes population growth harder to come by and slow if it occurs at all. A county experiencing natural decrease first has to attract enough people to move in every year to make up for population lost to its birth-death deficit before it can even begin to grow. Many Virginia counties experiencing natural decrease manage to do this most years, but because natural decrease is typically the result of a disproportionately large older population, it is a condition that does not end readily. Hanover County on the northern edge of the Richmond Metro Area has seen its birth-death surplus shrink from 500 more births than deaths each year during the 2000s to just 12 in 2013. Yet Hanover has continued to grow at a steady, albeit slower, rate thanks to many retirees moving in from the Richmond area.

If the age projections the Weldon Cooper Center produced in 2012 for Virginia’s counties and cities prove accurate, most of Virginia’s localities will continue to grow older and natural decrease could likely become even more common. For good or bad, Dickenson and other rural counties may be the vanguard of a trend that Virginia will become more familiar with in coming years.