As remote work persists, migration surge continues in 2023 for rural America

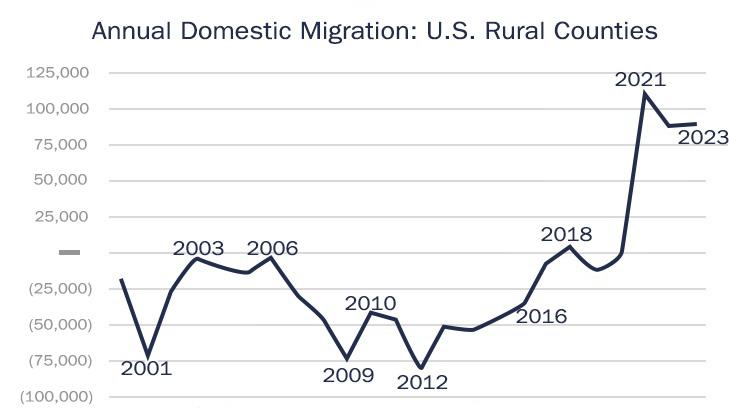

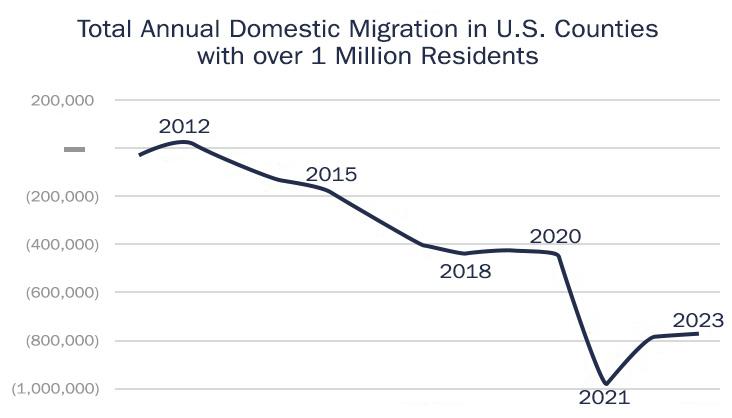

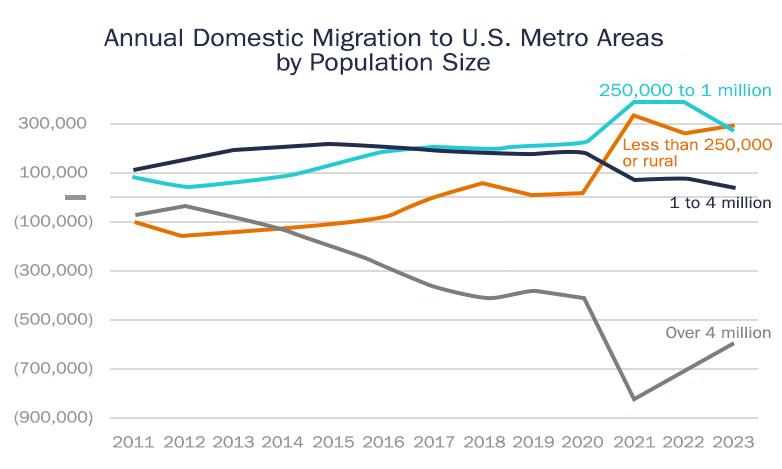

Recently, the Census Bureau released its 2023 population estimates for each county in the United States, showing many of the same distinctive demographic trends as in our Virginia 2023 population estimates released in January. Most notably, migration from large metro areas and counties to smaller metro areas and rural counties has continued across the country. Migration out of counties with more than one million residents in 2023 remained nearly twice as high as before the pandemic, while migration into the country’s smallest metro areas and rural counties rose in 2023 from already near record levels in 2022. The Census Bureau’s 2023 population estimates show that instead of being an anomaly, 2020 increasingly appears to have been a demographic turning point for much of the country.

During the 1990s, America’s major cities began a significant demographic transformation, growing for the first time in decades after a long period of decline. In particular, young professionals helped drive growth in cities, attracted by the rich array of cultural offerings, innovative cuisine, as well as more diverse and affordable housing options. Niche market brands, such as Lululemon and Starbucks, emerged predominantly in large urban centers, epitomizing the new wave of retail that catered to affluent, highly educated consumers. In his bestseller Bobos in Paradise, David Brooks highlighted how Starbucks and other “zeitgeist-heavy institutions that cater to educated affluents” were instrumental in attracting young professionals to urban areas and as a result, some cities actually grew younger even as America aged. Washington DC was one such city; the 2010 Census showed that DC’s median age had fallen over the 2000s while the U.S. median age rose by two years.

Even before the pandemic, migration was shifting to smaller cities and rural areas

During the 2010s, population growth in most of America’s largest cities began to stall as their cost of living climbed, making them less affordable. This helped drive migration to medium-sized, more affordable metro areas, such Charlotte, Jacksonville, and Nashville. In 2000, the median rent in Washington DC was 10 percent cheaper than in Charlotte, North Carolina. However, by 2019 DC’s rent was over a third higher and its median home price 2.5 times higher than Charlotte’s. This shift in migration was supported by several other factors that developed during the 2010s: the rise of social media, which allowed smaller cities to quickly emulate and improve on the cultural and culinary offerings of larger ones. The expansion of e-commerce also helped. Services like Amazon’s one-day shipping became available to most of the population, equalizing access to products across the country. By the end of the decade, large metro areas with populations exceeding four million were losing 400,000 residents annually to other parts of the country.

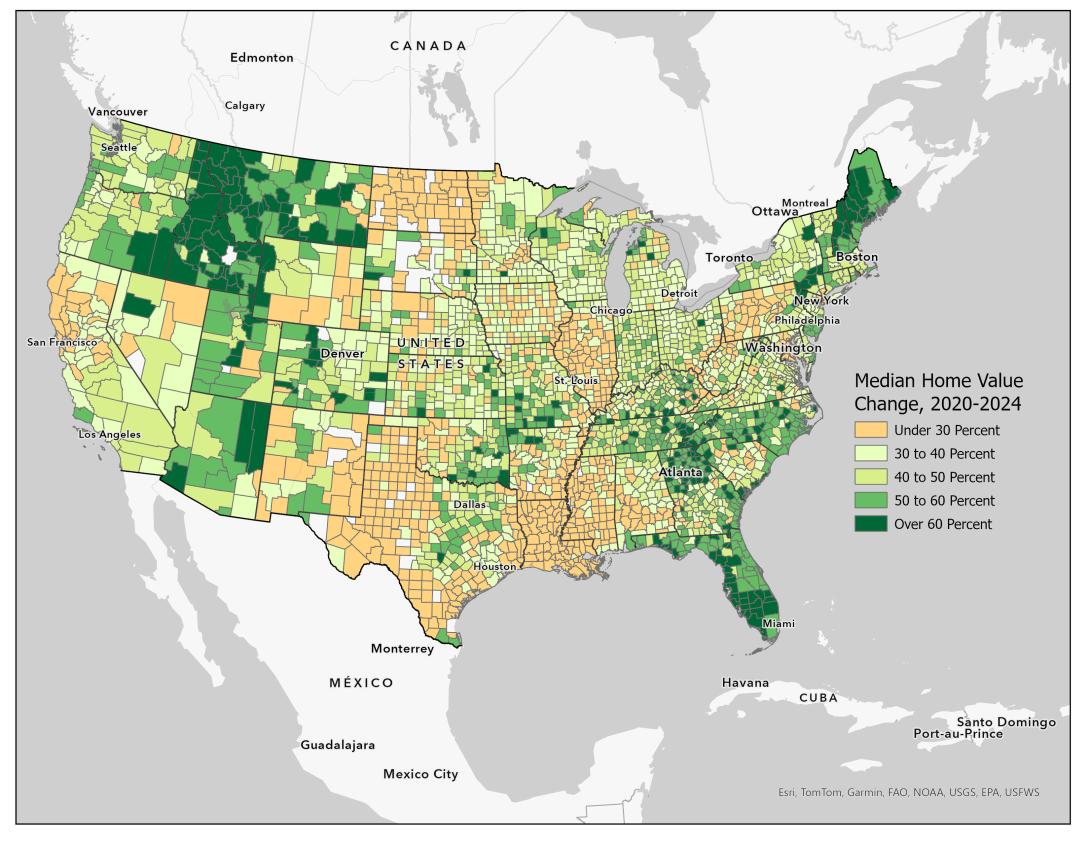

Source: Zillow Housing Data, home values are not counted for some small counties. Median value is calculated using the average for the six months prior to March 2020 and March 2024. The U.S. median home value rose by approximately 40 percent over this period.

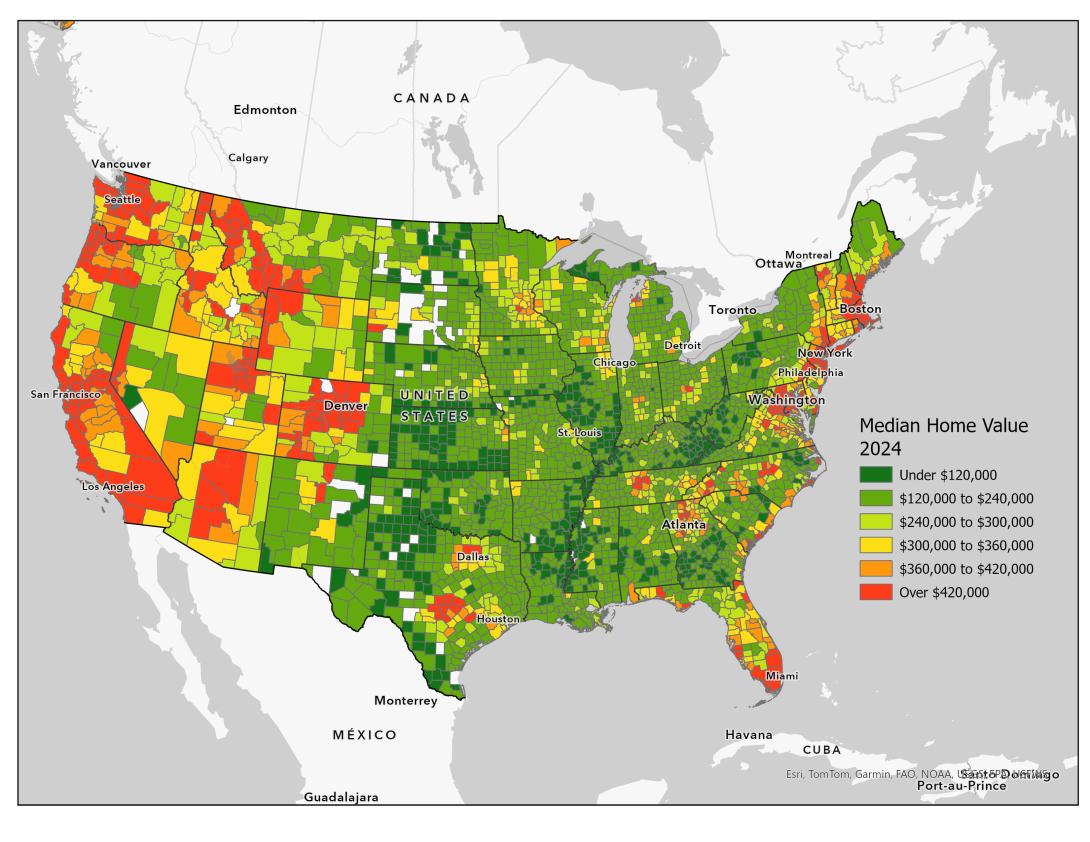

The pandemic simply accelerated migration trends that had already become established over the 2010s in much of the country. Migration to smaller, affordable metros areas with fewer than one million residents, like Knoxville, Tennessee, doubled during the first year of the pandemic while migration out of the largest metro areas also doubled in 2020. At the start of the 2010s, the Knoxville Metro area attracted 3,000 more people annually than it lost to other parts of the country. By 2019, the number had risen to 7,000 before reaching over 14,000 during the pandemic. Some of Knoxville’s new residents came from nearby areas but many traveled further, typically from higher-cost states like California. In 2015, Knox County had only 3 more people move to it from California than leave for the Golden State. In 2019, the number had grown from 3 to 253 and in 2021, it reached 1,261, making California the top source of out-of-state movers to Knoxville. With the surge in migration, home prices in Knox County rose faster than all but 35 other counties in the country, causing Knox County’s median home prices to exceed the national median home value for the first time last year.

Source: Zillow Housing Data, home values are not counted for some small counties. Median value is calculated using the average for the six months prior to March 2024.

Perhaps the most remarkable statistic in the 2023 population estimates data is that last year the country’s rural counties and smallest metro areas—those with fewer than 250,000 residents—became the top destination for people moving within the country for the first time in decades. Migration into these areas rose exponentially during the pandemic, and still, the net number of people moving to them rose again last year. Many of the small towns and rural counties that experienced a surge in new residents last year were places that are relatively attractive to vacationers, such as Georgetown, South Carolina, south of Myrtle Beach. But many other communities less well known to tourists also have seen a surge in new residents in recent years after years of out migration. Martinsville in southern Virginia is one of them. It was once known as “The Sweatpants Capital of the World” due to its now-closed textile mills, and during the 2010s, Martinsville was part of the poorest state senate district in Virginia. However, in recent years, it has experienced some of the strongest wage growth in Virginia. In 2023, the domestic migration rate into the Martinsville region was the second highest among Virginia’s metropolitan and micropolitan areas.

Remote work remains a key driver behind post-pandemic migration trends

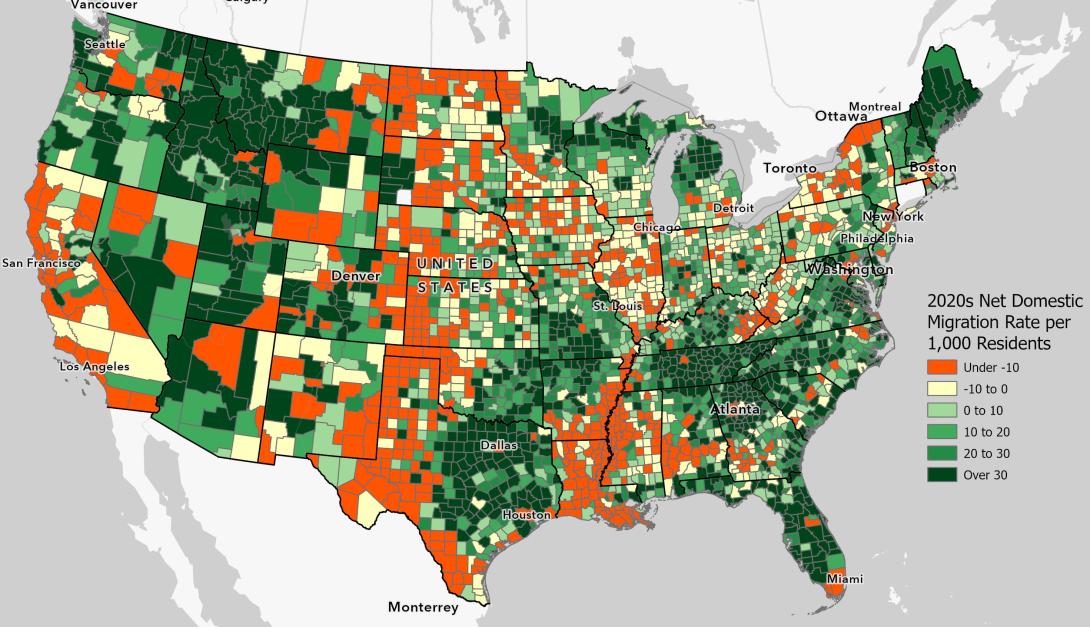

While the growth of remote work during the 2010s already appeared to be influencing where people moved, its explosion in 2020 has made it a key driver of domestic migration trends since then. With a third of workdays being done remotely in 2023, Americans have more geographic flexibility and have been increasingly willing to move far from large population centers if their destination offers a good quality of life. Communities that have easy access to outdoor recreation opportunities have seen a spike in the number of people moving to them. Areas of the country that attracted new residents at high rates in 2023 were those near large waterbodies, notably in the Southeast, Northern New England, and the North Great Lakes; and near mountains, particularly the Northern Rockies, the Ozarks, and the Southern Appalachians.

Source: Census Bureau Intercensal County Population Estimates 2020 to 2023 Components of Change. Connecticut counties are not included due to the state switching to planning regions.

If a significant share of work continues to be done remotely, some future historians will likely question why the migration trends that have become so prominent since 2020 didn’t develop sooner. In the 1970s and 1980s, researchers, including Alvin Toffler in his bestseller The Third Wave, predicted that the emerging information-based economy would enable much of the white-collar workforce to frequently or primarily work at home in what Toffler called “electronic cottages” —a shift from the longstanding factory-based work model followed by the vast majority of white-collar workers until 2020. Toffler predicted that such a shift would have far-reaching implications:

“We cannot today know if, in fact, the electronic cottage will become the norm of the future. Nevertheless, it is worth recognizing that if as few as 10 to 20 percent of the workforce as presently defined were to make this historic transfer over the next 20 to 30 years, our entire economy, our cities, our ecology, our family structure, our values, and even our politics would be altered almost beyond our recognition.”

The technology that made remote work possible was already widespread before the pandemic; in 2019 three-quarters of the population had broadband internet at home and a larger share had smartphones. Yet, employers were only slowly adopting remote and hybrid work arrangements. The proportion of work completed remotely in 2019 was a fraction the share last year and far less than Toffler had anticipated. The magnitude of the shift that much of society made to remote work in 2020 is something akin to a social revolution in the scale of its impact. While we are still coming to grips with its many implications, the Census Bureau’s 2023 estimates appear to show one result has been a significant change in where many Americans are choosing to live.

Consumer-oriented companies, such as Starbucks, have been among the first to adapt to the dramatically shifting demographic trends that began in 2020. Starbucks has closed hundreds of underperforming urban shops since 2020 and has opened hundreds of locations in small towns across the country that are attracting new residents. Since 2012, the proportion of new Starbucks locations in small towns has grown from 2 percent to over 20 percent in 2022. While Starbucks may not have the cachet that once attracted David Brooks’ attention, it still needs a critical mass of wealthier than average customers who appreciate its relatively expensive drinks to justify opening a new shop. In 2021, Starbucks opened its first store in Martinsville, Virginia, the former “Sweatpants Capital of the World,” and since then, a flurry of new Starbucks have opened in nearby small towns across southern Virginia, including Franklin, Galax, and South Boston—all communities that have drawn an increasing number of new residents in recent years.

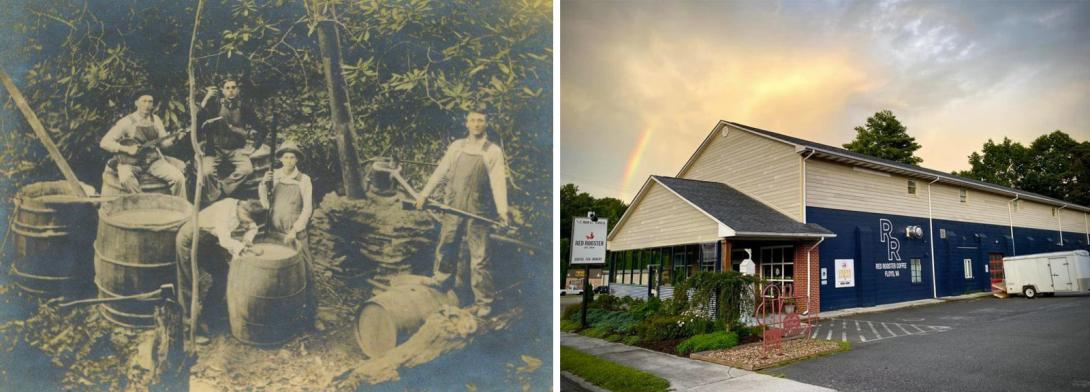

It wasn’t long ago that in most of rural Virginia it would have been harder to get a shot of espresso than a shot of Virginia’s homemade spirits. Over the last couple of decades, independent coffee shops have become so commonplace in small towns and rural counties across Virginia and the U.S. that it is taken for granted, as is the delivery of virtually any physical product via e-commerce, any type of streaming entertainment, and a wide array of other services, including telehealth and online education. Over the last couple of decades, there has been a growing perception that America is becoming geographically and culturally divided, but there has also been a convergence in tastes and increasing access to the same products, media, and services. This convergence helped create the conditions that made millions of Americans more willing, in recent years, to move to small cities, towns, and rural counties across the country. If the adoption of remote work turns out to be as transformative as Alvin Toffler expected, then we are likely only at the beginning of a multi-decade period marked by many substantial societal changes. The Census Bureau’s 2023 estimates provide us with some clues for what the rest of the 2020s may look like.