High cotton: When Virginia’s counties hit their peak

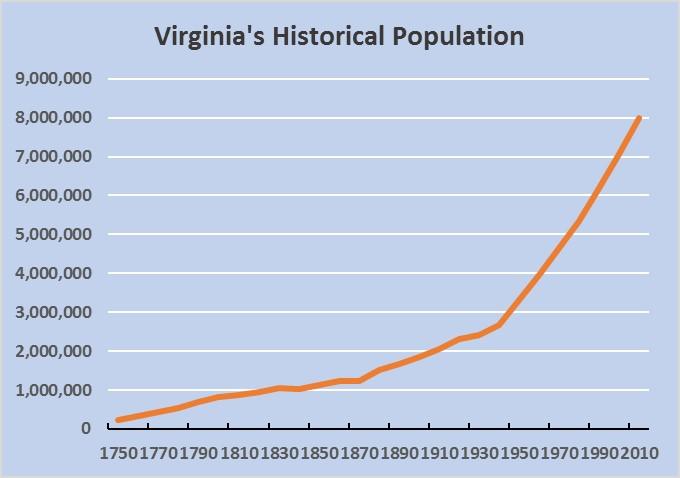

If you grew up in one of Northern Virginia’s suburban counties, such as Prince William, or in any of Virginia’s metro areas, you likely grew up with the impression that growth is as certain as the seasons. For decades, many counties in Virginia have grown relentlessly, constructing thousands of homes each year to house new residents. With more residents come more schools, roads, offices and shops. Except for the hard times around the Civil War, Virginia’s population as a whole has grown continuously since it was a colony.

But outside Virginia’s largest urban areas, population growth is not a fact of life. In 2013, the population of most of Virginia’s counties and cities had declined from when it peaked in the past.

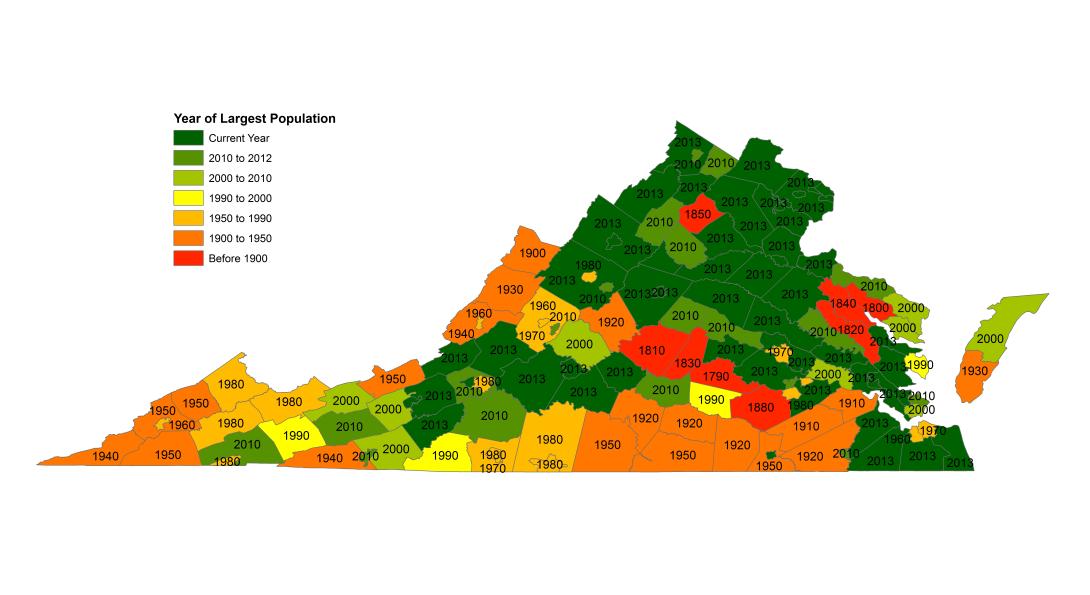

The reasons why each county and city’s population peaked and then declined are as varied as the different decades in which they reached their largest size. Understanding the trends of each period helps us get at the reason why most counties and cities in Virginia have declined in population.

The lost century

An overreliance on Tobacco as a cash crop in the Piedmont and Tidewater had depleted the soil of many eastern Virginia farms by the early 1800s. As tobacco production fell, fewer workers were needed for the labor intensive process of growing and processing tobacco, fueling an exodus from eastern Virginia. Henry Ruffner, the President of what is now Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, estimated that more people had moved out of eastern Virginia between 1790 and 1840 than all of the original states north of Maryland.

In Prince William County, the slow shift from Tobacco farming to more sustainable crops, such as Wheat, caused a similar dislocation in workers, many of whom were slaves. By the start of the Civil War, Prince William County’s population had declined more than a third from its peak in 1800. When the painter Lefevre James Cranstone traveled through eastern Virginia just before the war he found many of the great plantations crumbling and their fields empty. The widespread displacement from war and the abolition of slavery would cause Prince William County’s population to decline by another 12 percent during the decade.

Winners and then losers in the New South

When Virginia’s economy recovered after the Civil War, the population of many eastern Virginia counties also began to grow again. Improved agricultural practices and mechanization made farming more profitable. As industrialization intensified in Virginia, villages with access to waterpower and railroads expanded. By 1920, the population of many counties in eastern Virginia, including Prince William County, finally surpassed their previous highs from a century earlier.

Though improved transportation and industrialization fueled the growth of Virginia’s villages and towns, it also meant that its economy was increasingly in competition with other markets. Farming had been the foundation of rural counties’ economies, with many villages formed around a flour mill. But most crops, including wheat, could be grown and harvested more efficiently on the Great Plains or in California’s Central Valley. Similarly, the opening of Coal Mines after the Civil War caused many southwest Virginia counties to grow tenfold in population within a few decades. But increasing mechanization meant that by the early 20th century less labor was needed for mining. During the first half of the 20th century, many counties that had prospered during the decades after the Civil War, in Southwest and Southside Virginia as well as in the Allegheny Mountains, entered a long period of declining population that has continued to today.

Independent Cities

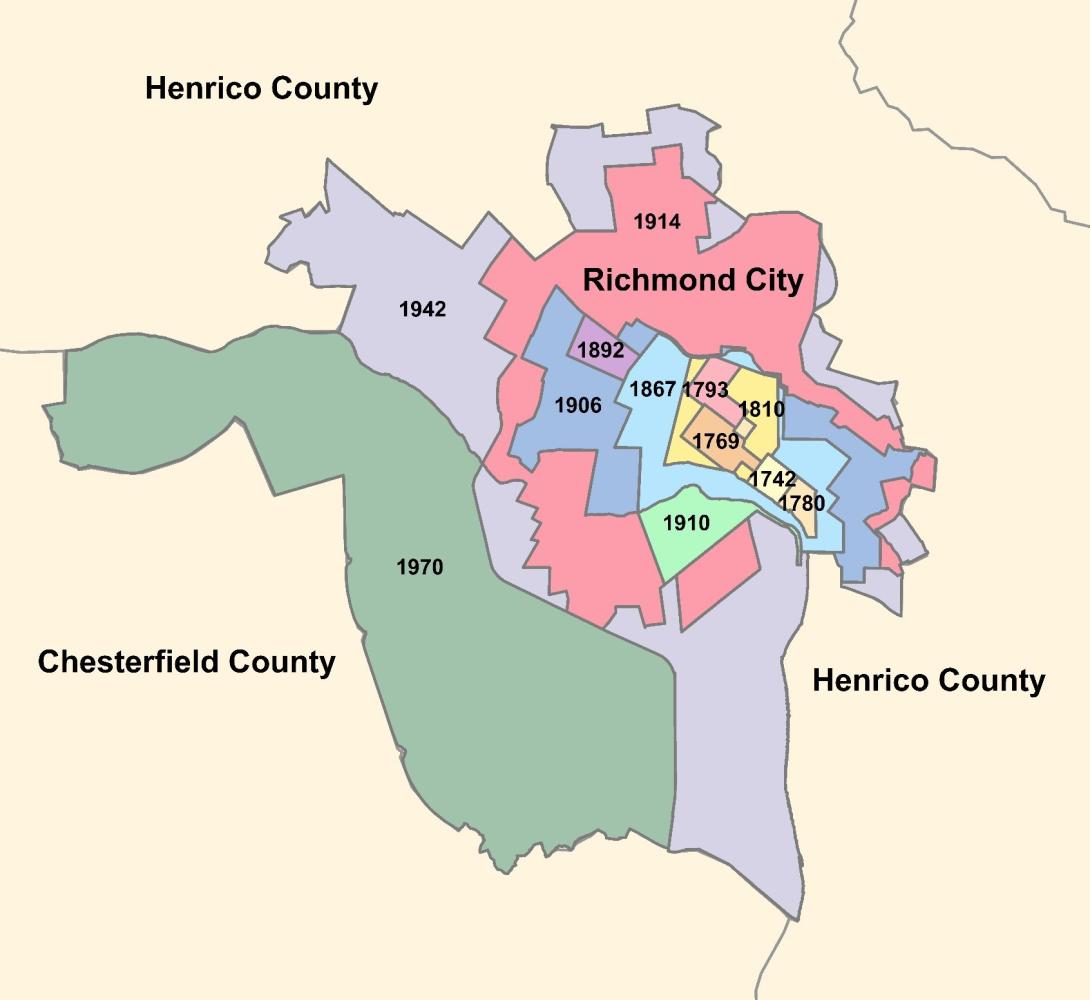

Many of those leaving Virginia’s rural counties at the turn of the century were moving into its cities. Along harbors and at railroad junctions, villages grew to cities within a few decades. Roanoke was nicknamed the “Magic City” because it swelled from a village of 500 to a city of over 20,000 in just a decade. Despite its near destruction during the Civil War, Richmond grew at torrid rate after the war, with its population increasing by roughly a third each decade till 1920.

The rise of cities after the Civil War forced Virginia to reorganize its local government structure to accommodate them. In most states, city governments simply offered extra urban services such as water and sewer, while counties provided a base layer of public services, such as courts and schools, to residents living both inside and outside city limits. But because most of Virginia remained deeply rural with counties providing few basic services, the state decided that incorporated cities would be completely independent from their rural parent counties. An Independent City would essentially be a county within a county, providing both urban services, such as water and sewer, as well as basic county services, including courts and schools.

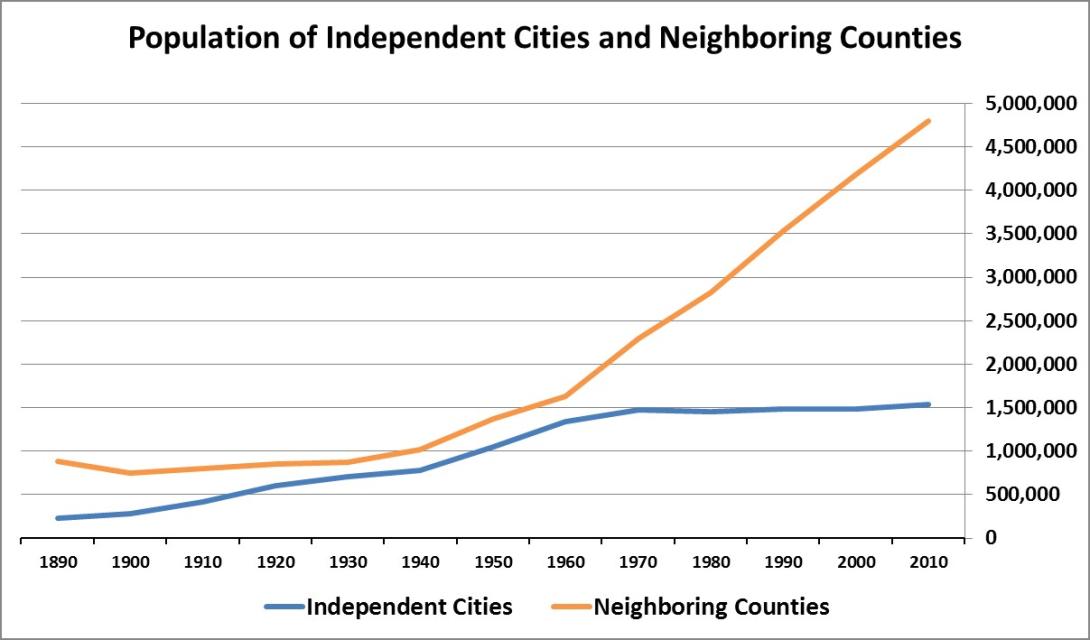

Initially the Independent City system worked well. As urban areas developed in counties, they were annexed by neighboring cities or often made themselves into cities. But once counties began developing services for their urbanizing neighborhoods, they were motivated to fight attempts by independent cities to annex their tax base. By the 1970’s most cities were no longer allowed to annex their suburbs and cities’ populations began to decline as families increasingly moved out to suburbs in neighboring counties.

A future of decline?

As the map at the beginning shows, a good number of Virginia’s counties have begun to decline in population in recent years, most of them are rural. In some cases, their decline in population may be just a short pause in growth. Demographic trends have been particularly hard on rural counties since the beginning of the recession. Though many rural counties in Virginia are now attracting more people than those leaving, most also have more deaths than births, which often cancels out any gains from migration. Given that most rural Virginia counties have low birth rates and large older populations, growth may be harder to come by for them.

In 1900, Highland County, in Virginia’s western Allegheny Mountains, had closed out the 19th century by reaching a new high in population, while Prince William County ended a century of slow growth and decline in population. Few would have expected Highland County to lose half its population in the next century and for Prince William County’s population to increase by 2500%.

Predicting future population change may be difficult, but population growth doesn’t automatically turn counties into some sort of winners, anymore than population decline makes counties losers. Prince William County’s growth is in large part due to the many opportunities, particularly jobs, that living there provides access to. Population decline in many counties is often related to their lack of jobs. But as the previous post highlights, the large number of retirees that are attracted to rural counties, indicates that many counties past their peak population, continue to have a lot to offer.