America’s College Promise in Virginia

On Friday, January 9, President Obama announced America’s College Promise, his new vision for US community colleges, at Pellissippi State Community College in Knoxville, Tennessee, having released this teaser just the day before.

In its press release on the plan, the White House explained its proposal to make community college “free for everybody who’s willing to work for it.” Under this plan, community college tuition would be covered for students enrolled at least half time, with a 2.5 GPA or better. President Obama proposes that three-quarters of the cost of tuition would come from the Federal Government, while states who participate would be expected to cover the remaining quarter.

Tonight in the State of the Union address, we can expect to hear more from him on this plan–and are certain to hear a pitch for its funding. Here are some things to keep in mind when the topic comes up.

Community College in Virginia

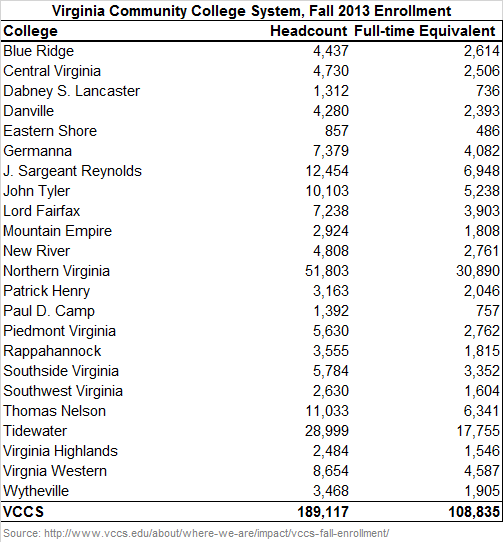

The Commonwealth has a network of 23 community colleges ranging, in 2013, from a fall enrollment of less than 1000 at Eastern Shore Community College to over 51,000 at Northern Virginia Community College. (The number taking a class at any point during the year is quite a bit higher than this, since many such students enroll at some point other than the fall.)

The Virginia Community College System (VCCS) website explains that “If you are in Virginia, you are just 30 miles from a community college,” where average annual tuition is just over $4,000.

The finances of the thing

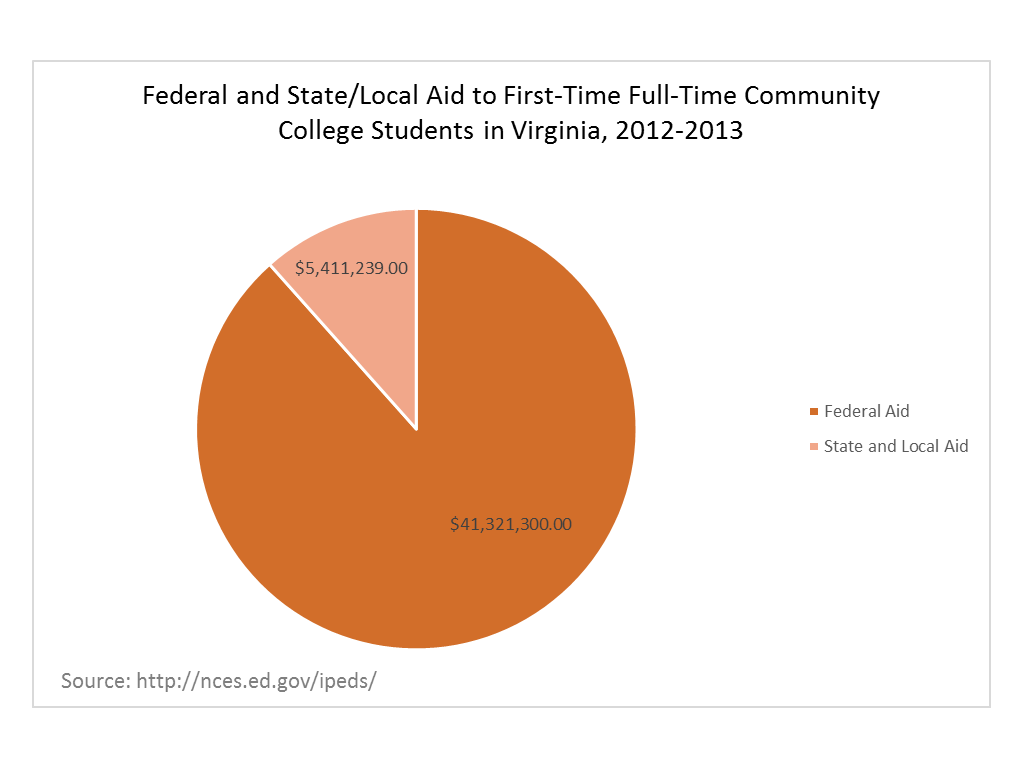

To get a better handle on what America’s College Promise Proposal might look like, let’s take a look at first-time full-time students’ financial aid across VCCS for the 2012-2013 school year. This is an imperfect approach to thinking about President Obama’s plan, as he proposes that all students enrolled at least half-time get the tuition benefit–but the data are more reliable for full-time students’ enrollment. We don’t know whether first-time full-time students will stay enrolled full-time throughout their community college career, or whether they’ll achieve the required minimum 2.5 grade point average that President Obama’s plan will require. However, we do know–thanks to great data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System–that the amount of federal aid first-time full-time VCCS students received in 2012-2013 was just over $41 million, while the state and local aid to these same students totaled to slightly less than $5.5 million.

Let’s consider what funding for the 2012-2013 school year might have looked like under the cost-sharing proposed in the America’s College Promise plan. Using tuition and fees data for each of the colleges in question, it would have cost the Federal Government about $51 million to foot 75 percent of the total tuition + fees bill for first-time full-time students for one year. The remaining quarter, to be covered by the Commonwealth, would have totaled to about $17 million. Assuming that in the 2012-2013 school year, there were equally as many second-year students on the full-time track with the required GPA, the total cost to the federal government under the proposed plan would have been slightly more than $100 million for full-time students; the Commonwealth would have had to pick up the remaining $34 million on the tab (again, for full-time students alone).

Yes, these numbers look large. They are. But more interesting than the actual dollar amount is the relative change in aid provided to students. In 2012-2013, the state/local-to-federal aid ratio was about 1-to-7.6. Under the proposed plan, the state-to-federal ratio would have been, by rule, 1-to-3. While both parties would have had to contribute more in absolute terms, Virginia would have had to contribute relatively more.

How realistic are these numbers?

Now that I’ve given you some figures based on past data, let me gracefully hedge my bets by raising some important points about what we really just don’t know about the proposed plan.

First, how many students are going to fit President Obama’s requirements for responsible students? Across Virginia’s community colleges, among all students who entered in 2009 with the intent of obtaining a diploma or certificate, only about one in four graduated by summer 2013. In other words, only 25 percent of students who entered with the intent of completing a degree or certificate program maintained at least a half-time schedule, taking steps toward graduation. An even smaller percentage–about one in nine–graduate in two years. Even though we’re only considering full-time students in the calculation above, these completion rates would still suggest that our estimates are probably too high.

That said, we don’t know how the promise of free tuition will change students’ motivation to stay enrolled at least part time, with moderate GPAs, making steady progress toward graduation. Other aspects to the proposal–perhaps most importantly, the charge for community colleges to make specific, evidence-based efforts to improve student outcomes including, for example, “academic advising and supportive scheduling”–might have an effect on student persistence, as well.

The promise of a long-term benefit?

In its initial press release on the topic, the White House states that “[b]y 2020, an estimated 35 percent of job openings will require at least a bachelor’s degree and 30 percent will require some college or an associate’s degree.” (This information likely comes from a June 2013 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce publication.) In other words, President Obama is suggesting that a high school degree is, in general, no longer sufficient for individual workers to compete in the labor market–and that a country of high-school graduates is no longer competitive in the global economy. The idea is to extend free public education beyond grade 12, so that by the time individuals leave the umbrella of the public school system, they have the tools need for success–either in the form of credits transferrable to a 4-year university, or specific credentials for employment.

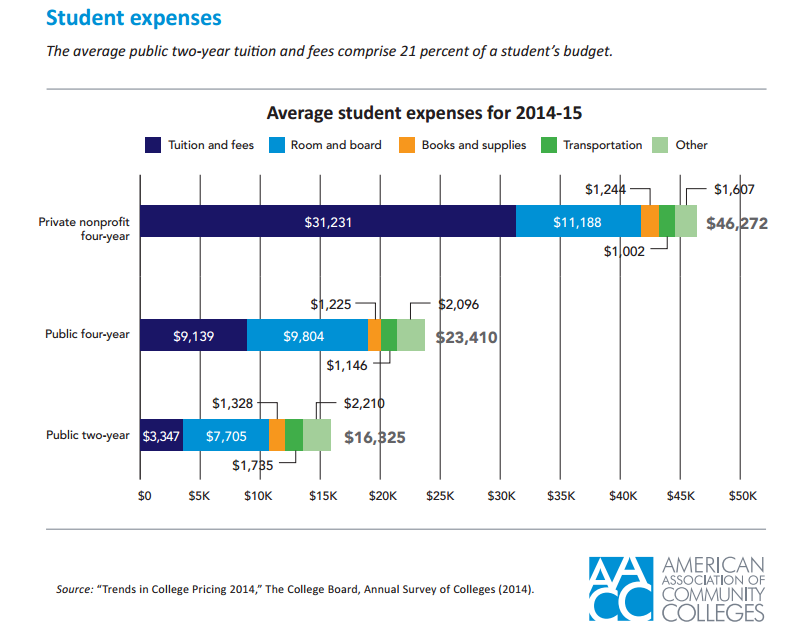

Keeping in mind that not everyone agrees that all students should go to college, in the first place, let’s tackle a slightly more tractable concern: Even if community college were made tuition-free, students would still bear some cost of attendance. In fact, for students enrolled in communities colleges, tuition accounts for a smaller percentage (about 20 percent) of total student expenses than it does for students enrolled in either public (40 percent) or private (over 65 percent) four-year universities.

In other words, tuition assistance certainly reduces the financial burden of community college, but does not address all of the financial needs a community college student likely faces. And it’s also important to keep in mind the additional cost to the student of reduced wages during the time of enrollment. If a student’s balance sheet doesn’t balance in the short-term, even with the promise of free tuition, then might be difficult for her to weigh the potential long-term benefit of completing a degree or certificate program.

Will Congress support America’s College Promise with the funding it will require, an estimated $60 billion over 10 years? It’s already been greeted with a fair amount of skepticism. There are, evidently, many cost-benefit analyses that must conducted in order to determine whether America’s College Promise can, or should, be kept. Perhaps, however, one benefit has already been brought to bear: conversation and debate over whether and why we care about community college access and persistence, who stands to benefit from changes and improvements to the system, and how we can get more students to successfully complete certificate or degree programs.