Jobs and Gender

I spend a lot of my time working on projects for the Office of Career and Technical Education at the Virginia Department of Education. CTE receives a significant portion of its funding from the federal government, and like all government funds it comes with strings attached. For the last 25 years one of the most important of these has been the requirement to equalize the gender balance of students enrolling in and completing courses. Penalties are exacted when courses in traditionally male fields, like engineering, have fewer than 25 percent females, or courses in traditionally female fields, like nursing, have fewer than 25 percent males. Schools have succeeded in equalizing enrollment in some areas, but in others, this goal is extremely difficult to meet. The Accounting and Computer Information Systems courses enroll almost equal numbers of male and female students, but few Pre-engineering or Cosmetology courses meet their 25% target. CTE has trouble meeting this goal not because of lack of effort, but because their enrollment patterns follow the job trends in society at large.

| What is CTE |

| Career and Technical Education is the new term for what used to be called vocational education, a change that was made as high schools changed the range and intention of courses taught in this program. Vocational courses were primarily hands on and designed for students going right to work after high school in jobs like carpentry and auto mechanics. Today CTE teaches a much wider range of courses. Skilled trades are still important, but the majority of students are in other programs including, accounting, health sciences, pre-engineering, and information technology. Seventy-five percent of CTE graduates go on to college, with about half going into four year colleges and the half to community college. |

The second half of the 20th Century saw an upheaval in gender roles. From the 1950s through the 1980s, women poured into the labor market, especially into jobs in the then growing managerial, professional, and sales sectors. Step into a professional meeting today in a bank, or a law firm, or an advertising agency, and it’s instantly obvious that you’re not in the 1950s or 1960s.

But the gender mix has not changed in all jobs equally. Visit a construction site or a nursing home and apart from the clothes, you might not be so sure that you’re in the 21st Century. These sectors are not much less gender segregated now than they were sixty years ago.

Occupations and Gender, 1950-2000

The method of classifying occupations and counting employment has changed several times since the 1950s, so it is not possible to make a precise comparison between occupations across the decades. Nonetheless, the table below gives a rough idea of how the gender distribution in major occupational groups changed from 1950 to 1980 to 2000. We see that:

- The managerial, professional, and sales groups become more evenly balanced from 1950 to 1980 to 2000.

- The gender balance in the service group changed somewhat toward the female.

- The clerical group, which was majority female in 1950, became even more so by 2000.

- The trades and other blue collar occupational groups experienced relatively little change, remaining strongly majority male.

| Percent Female in Makor Occupational Groups | |||||

| 1950 | 1980 | 2000 | |||

| 9% | Managers, officials & proprietors, inc farm | 31% | Executive, administrative, & managerial | 36% | Management |

| 54% | Business & financial operations | ||||

| 39% | Professional, technical, & kindred | 49% | Professional specialty | 56% | Professional & related |

| 34% | Sales workers | 49% | Sales occupations | 50% | Sales & related |

| 45% | Service workers except private household | 59% | Service | 57% | Service |

| 62% | Clerical & kindred workers | 77% | Administrative and support | 75% | Office & administrative support |

| 19% | Farm laborers & foremen | 15% | Farming, forestry & fishing | 21% | Farming, fishing, & forestry |

| 3% | Craftsmen, foremen, & kindred workers | 8% | Precision production, craft & repair | 3% | Construction & extraction |

| 27% | Operatives & kindred workers | 27% | Operators, fabricators & laborers | 32% | Production |

| 4% | Laborers except farm & mine | 16% | Transportation & material moving | ||

| 5% | Installation, maintenance, & repair | ||||

| Source: Decennial Census, 1950, 1980, 2000 | |||||

It is difficult to analyze the changing gender balance in specific occupations between 1950 and 2000 because the occupational landscape has changed so radically. The 1950 Census reports on dozens of occupations that are no longer measured, including: Credit men, Floormen, Express messengers, Elevator operators, Hucksters and peddlers, Newsboys, Porters, Loom fixers, Asbestos workers, Laundresses (both living in and living out) and many more. And of course the 2000 Census reports on dozens that were not mentioned, or even in existence, in 1950, including: Logisticians, Software engineers, Nuclear technicians, Paralegals, Dental hygienists, Physical therapists, Security system installers, Semi conductor processors, and more. However, where direct occupational comparisons are plausible, we see that change fits the pattern shown above, the stereotype with which we are now familiar.

- Within the Professional group, engineering occupations remain majority male. Chemical and Civil engineers were under 2 percent female in 1950. They reached 6 and 8 percent female by 2000.

- Many non-engineering professions, on the other hand, began to equalize. Veterinarians shifted from 6 percent to 39 percent female; Social scientists from 32 to 50 percent; Physicians and surgeons from 6 to 31 percent; and Optometrists from 6 to 54 percent.

- The majority female healthcare occupations remain majority female. Registered nurses shifted from 98 to 91 percent female and Practical nurses from 96 to 92 percent.

- Professional sales occupations added many women. Real estate agents went from 14 to 58 percent female and Securities sales agents from 10 to 39 percent.

- Clerical occupations tended to remain majority female or become even more so. Secretaries shifted from 94 to 97 percent female, Bookkeepers from 77 to 90 percent, and Library attendants from 74 to 98 percent.

- Individual blue collar occupations remained majority male. Automotive mechanics, Carpenters, and Electricians, were all about 1 percent female in 1950. Electricians reached 3 percent female by 2010, but Carpenters and Electricians stayed at 1 percent.

Gender Balance, 2010-2020

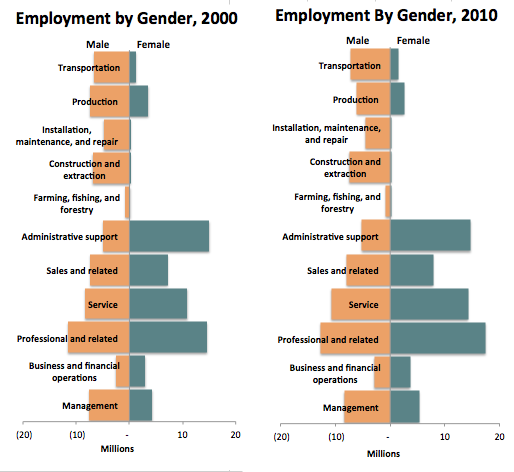

The 21st century is not so far seeing any change in this pattern. The charts below show the number of men and women employed in 2000 and 2010 in each of the eleven major occupational groups covered by the Census. Despite the economic upheaval and job loss over the past decade, the blue collar sector remains majority male and the Administrative Support group remains primarily female, while the Management, Professional, and Sales groups remain more evenly split.

The Census provides more detailed breakouts of occupational groups in the large Professional and Service sectors. The table below shows what while each group as a whole is relatively balanced, some subgroups persist with the imbalances they have shown since the 1950s . The Architecture & Engineering, Computer & Mathematics, and Protective Service subgroups remain dominated by men while the Education, Healthcare, and Personal Service subgroups remain dominated by women.

In other words, despite the influx of women into the workforce since 1950, significant efforts to eliminate gender segregation, and significant success in some areas, two gender stereotypes persist in actual employment patterns. Occupational groups that have a large personal service component tend to be majority female, while technical and manual occupations tend to be dominated by men, patterns that have held steady for many years.

| Percent Female in Professional and Service Subgroups | ||

| 2000 | 2010 | |

| PROFESSIONAL OCCUPATIONS | 56% | 58% |

| Architecture and engineering | 13% | 15% |

| Computer and mathematical | 30% | 27% |

| Life, physical, and social science | 41% | 45% |

| Arts, entertainment, and related | 48% | 47% |

| Legal | 47% | 53% |

| Community and social services | 60% | 62% |

| Education, training, and library | 75% | 74% |

| Healthcare practitioners/techs | 74% | 75% |

| SERVICE OCCUPATIONS | 57% | 57% |

| Protective service | 20% | 23% |

| Building and grounds | 40% | 40% |

| Food preparation and serving | 57% | 56% |

| Personal care and service | 79% | 78% |

| Healthcare support | 88% | 88% |

So What Does This Suggest for Efforts To Promote Gender Equality In Schools?

It suggests, first of all, that efforts to promote gender equality in schools haven’t had much of an impact. Twenty five years of pressure from the Perkins funding process on Career and Technical Education and community colleges (which also receive Perkins funds) haven’t greatly increased either nontraditional enrollments or nontraditional employment in the targeted fields.

Perhaps, therefore, it is time to do away with gender equity requirements in the Perkins Act. Perhaps the requirement to meet gender enrollment targets in CTE courses is simply an ineffective sort of social engineering that ultimately takes time away from the more important job of imparting skills and improving opportunities. Perhaps we should direct our scarce resources elsewhere.

But perhaps not.

While I think it is misguided to punish schools for failing to meet the 25 percent nontraditional target in fields that have failed to even approach this in the actual workplace, I also believe firmly in the importance of insuring that every course is welcoming to both genders. It requires conscious effort to do this even for those who don’t intentionally discriminate. If you never have any girls in your pre-engineering program, it’s easy go ahead and schedule classes in that room back over on the other side of the gym where the football team practices. If you never have any guys in your nursing program, it might be easy just to close the guys’ bathroom in that corridor when it develops a leak. It’s easy to schedule male speakers to come into robotics class because because they’re easier to find, or take the health science class to the local nursing home instead of getting them into the emergency room where the male nurses are more likely to be found.

We may never see, and almost certainly don’t need, an equal division of genders in every occupation. But if students are to make informed choices about careers and future education they need the chance to explore without prejudice or exclusion. Keeping nontraditional pathways open will always require extra effort and commitment. Without this effort, the minority can so easily be excluded from opportunity.