Census 2020 may count everyone in the right place, but we won’t see it in the reported results

The 2020 Census is currently underway, and its accuracy relies on two equally important processes: complete data collection, and accurate data reporting. Complete data collection (in the words of the Census Bureau, “counting everyone once, only once, and in the right place”) is essential to an effective decennial census, which is estimated to cost $15.6 billion and which guides the allocation of more than $675 billion to states, communities, programs, and organizations.

Please note “guides the allocation” in the second half of the previous sentence, as the complete data collection is only part one of an accurate Census. Part two, accurate data reporting, drives the allocation of those funds (often awarding a certain amount of funds per person counted in each place), and also informs planning and service provision to citizens across the country. It tells local leaders how many school children to expect for the next year; rescue squads how many ambulances to have on hand; businesses how many working-age people might be available to fill their jobs.

Alarmingly, even if data collection in this Census is complete and perfect, the data released will be far from accurate due to the implementation of a new approach to data privacy named by the Census Bureau as “Differential Privacy Disclosure Avoidance System” (DP).

WHAT IS DIFFERENTIAL PRIVACY?

Differential Privacy is a new mathematical procedure in which all data below the state level (anything pertaining to counties, cities, or towns) will be infused with “noise” in pursuit of the goal of greater privacy protection. Sounds good, until it becomes clear that privacy protection comes at the great cost of data accuracy and utility.

On October 30, 2019, the Census Bureau posted 2010 data altered with the proposed DP procedures for 2020. This was designed to help data users better understand the 2020 Census disclosure avoidance system and to evaluate its impact on data quality. Analyzing the differences between the 2010 count and the 2010 noise-infused data (referred to as DP onwards) for the case of Virginia highlights several issues.

[Download Handout here: How Differential Privacy Harms Census Data in Virginia]

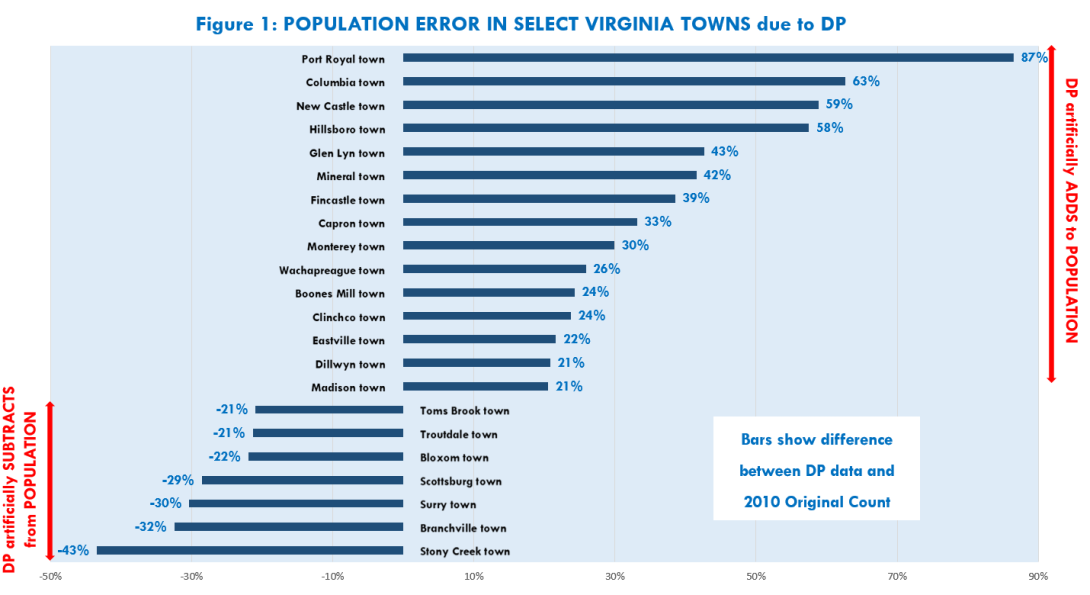

DP alters TOTAL POPULATION data in Virginia

Total population numbers for each city and county in Virginia have been reallocated in the DP data. Most larger localities are being underestimated and appear to have lower population numbers in the DP proxy data, while the converse is true for cities and counties with smaller populations. The most striking impact is within smaller towns in Virginia, which see dramatic shifts in their total population as a result of applying DP. For instance, Port Royal town nearly doubles (87% increase) from 126 residents in the original Census count, to 235 in the DP version. Columbia town with 83 residents originally, is allocated a population of 135 individuals, reflecting a 63% difference from its true count.

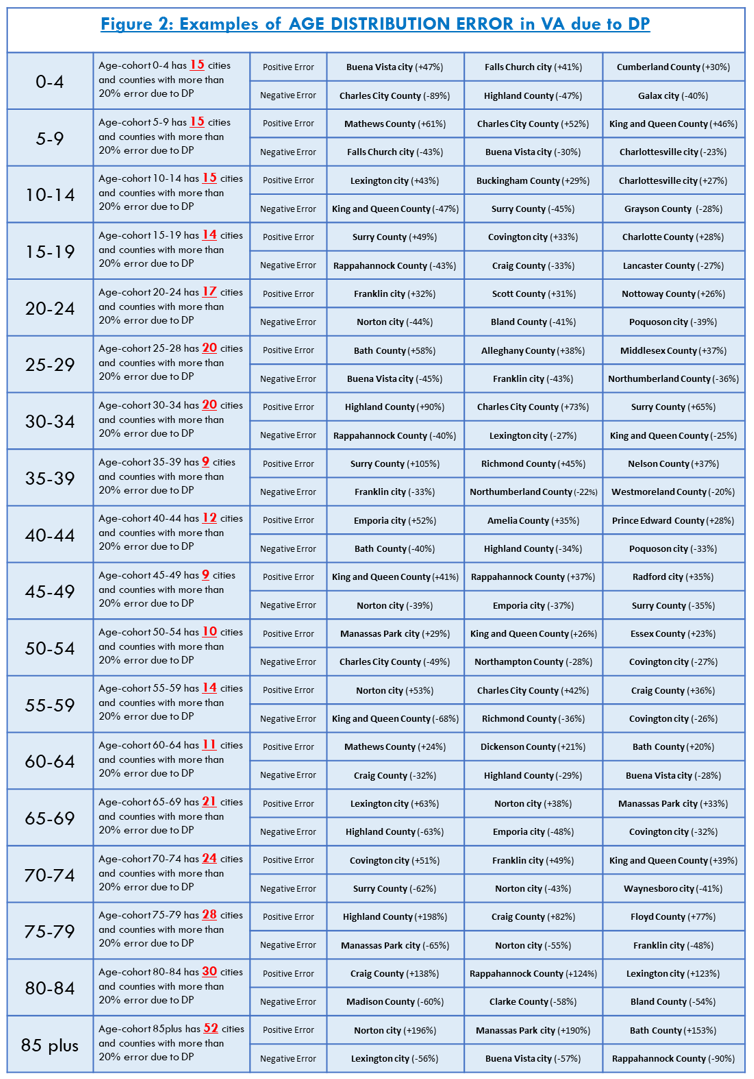

DP distorts AGE-DISTRIBUTION data in Virginia

While age distribution at the state level is similar between the 2010 count and the DP proxy, the data is significantly different for smaller geographies. Of the 133 counties and county-equivalent independent cities in Virginia, most localities have severe changes in their age-distribution at the 5-year cohort level, and this discrepancy remains even after aggregating to 10-year age intervals.

Data for young children in Virginia is severely distorted, and will affect forecasting for elementary schools or investments in early-childhood development. For instance, children ages 5-9 are over-estimated by 61% in Matthews County, while being under-estimated by 43% in Falls Church city.

For the 85 plus population, the DP data over counts by more than a 100 percentage points in Bath (153%), Highland (135%), Sussex (110%), and for Manassas Park city (190%) and Norton (196%), the errors are close to double that; putting at risk any planning issues related to senior health or elderly care that rely on Census data.

The data distortion might misrepresent a locality’s population structure altogether, such as Charles City, Craig, and Surry, as all three see considerable fluctuation in the age-distribution in DP data. For instance, children under 5 are under-counted by nearly 90% in Charles City, while those aged 80-84 are over estimated by 138% in Craig, and Surry sees an unexplained 105% increase in their 35-39-year-old cohort. King and Queen county has 12 of its 18 five-year age groups altered by 25 or more percentage points in the DP data, making the resulting age structure entirely dissimilar to the original census count.

DP even alters SEX-COMPOSITION data in Virginia

In certain cases, the noise-infused data dramatically modifies the age-sex makeup of a community. Several localities in Virginia are affected by this distortion, but the case of Highland County deserves special mention. Home to over 2,300 people, according to the 2010 DP data the county seems to have lost all men between the ages of 10-14 and 25-29. The original count data shows a relatively symmetric distribution of men and women, especially for the younger cohorts, with longer female life expectancy showing up as expected in the older age groups. The DP data on the other hand, is highly asymmetric and shows a disproportionate number of women ages 50-54 and men ages 75-79. The sex-ratio being altered from 100 to 73, and the population pyramid being reshaped in such an implausible manner, highlights the irony of the “shape your future” tagline chosen by the Bureau for its 2020 Census.

Overall, the differential privacy algorithm follows a certain pattern in its inaccuracy. Given that all the sub-groups must add up to the state control total which is fixed to the true count, the distorted data reallocates population from larger groups or high-density areas to small groups or sparely populated localities; for instance, urban to rural shifts, or shrinking larger categories in favor of smaller racial and ethnic groups.

In this era of big data analytics, concerns about individual privacy are well-founded. Compromises and concessions need to be made so that malevolent entities cannot manipulate or misuse data to target individuals. However, sacrificing data accuracy at the sub-state (region, city, county, town) level to such an extent that leads to misallocation of funds, poor planning, inadequate provision of services, or disadvantaging certain subsections of the population, is also a concern we cannot ignore.

The Bureau had good data protection measures in place for the 2010 Census, yet finds this Census particularly compelling as a time to undertake a big change in their practices. Ideally, finding a sweet spot in the accuracy-privacy tradeoff is a matter of great trade-craft, requiring the best minds and careful methods working through an iterative process with the Bureau and data users going back and forth to ensure the 2020 data released is viable and valuable. It appears that the Bureau is in a bit of a hurry to finalize DP, rushing through the discovery and testing process, unsettling the data user communities, inadequately justifying the significant change they propose to make, and moving ahead with haste and without adequate oversight to implement a flawed system. Should the Bureau proceed as planned, Census 2020 will yield data of questionable quality that are unreliable and unusable.

Census 2020 data distortion will have decade-long consequences, and we cannot retroactively reverse the damage done due to bad data and the resulting bad decision-making. Within Virginia, it will affect our state’s official annual population estimates and school-age children estimates, our ability to project future population by age and sex will suffer, and we will be unable to fully support and serve the everyday data needs of the citizens of the Commonwealth.