After a decade of slow growth, many of Virginia’s exurbs are booming again

Before the Great Recession in the late 2000s, Louisa County was among the fastest growing counties in the nation. Lake Anna’s 200 miles of shoreline helped attract thousands of retirees to the county, while Louisa’s low cost of living and proximity to Charlottesville, Northern Virginia, and Richmond attracted many younger residents willing to make a long commute to the metro areas. After a decade of slow growth in population following the 2000s housing crash, the 2022 Virginia Population Estimates that our center released show Louisa and many other counties located on the borders of Virginia’s metro areas are booming again.

| Fastest Growing Since 2020 | Fastest Declining Since 2020 | ||

| New Kent County | 7.5% | Buchanan County | -4.7% |

| Goochland County | 5.6% | Radford City | -4.6% |

| Louisa County | 5.4% | Henry County | -4.3% |

| Suffolk City | 4.9% | Sussex County | -4.2% |

| Chesterfield County | 4.5% | Patrick County | -3.1% |

| Caroline County | 4.5% | Dickenson County | -3.0% |

| Stafford County | 3.9% | Lexington City | -3.0% |

| Frederick County | 3.6% | Charles City County | -2.8% |

| Clarke County | 3.6% | Greensville County | -2.7% |

| Spotsylvania County | 3.4% | Smyth County | -2.7% |

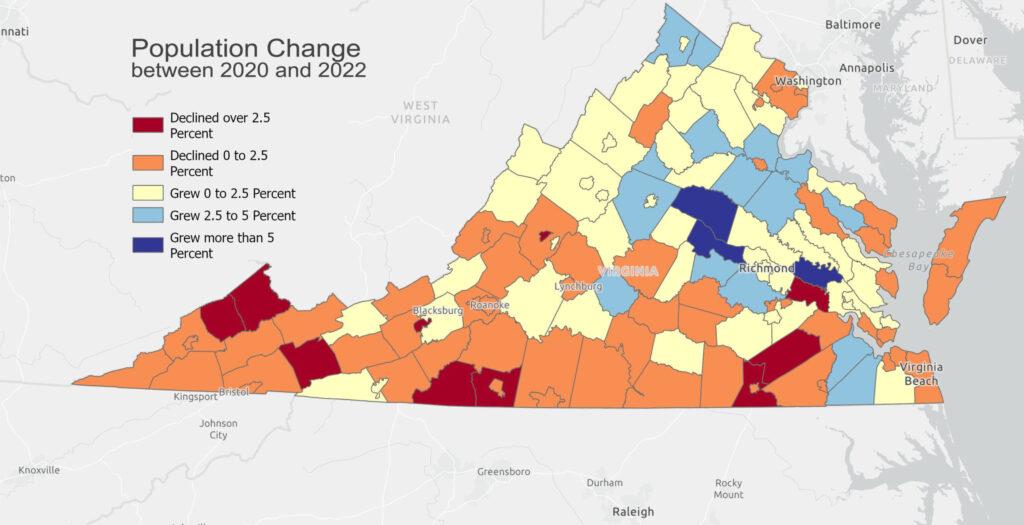

Since the 2020 census, most of Virginia’s cities have lost population, but localities located on the edge of metro areas, five in particular, have become fast growing. The three fastest growing localities in Virginia were all located on the edges of the Richmond Metro Area, which has grown more than any other Virginia metro area since 2020. In Hampton Roads, Suffolk has been one of the few localities growing faster than Virginia as a whole, surpassing Portsmouth in size last year. In Northern Virginia, Stafford was the fastest growing locality in the region, surpassing Alexandria in size.

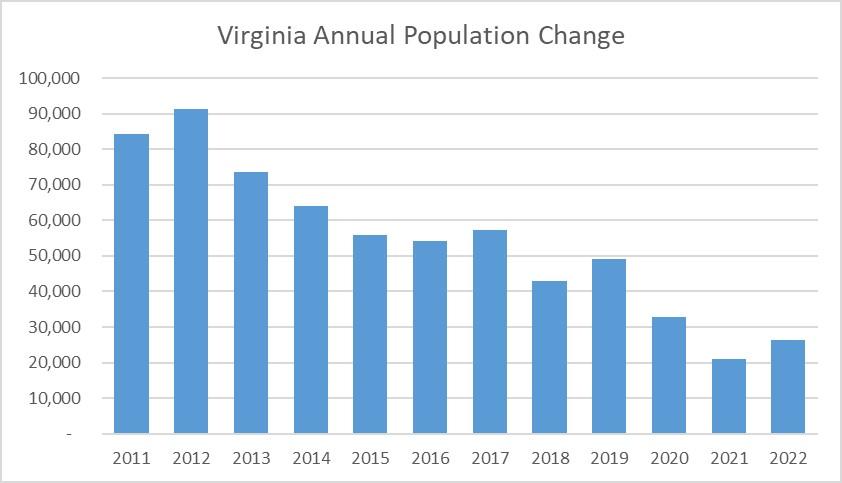

Virginia is growing more slowly than in previous decades

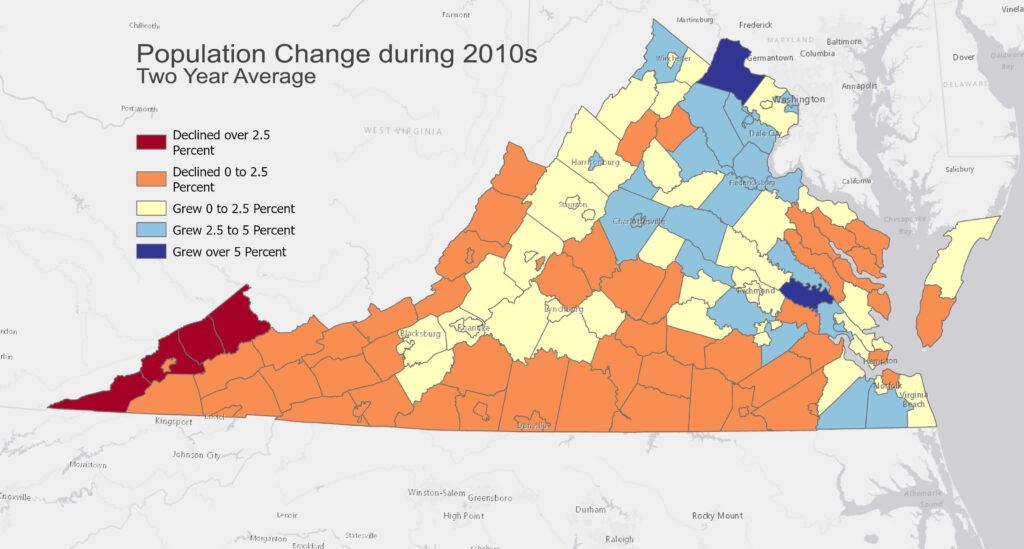

At first glance, a map of Virginia’s population change since 2020 may not appear very different from a map of population change during the last decade. Most of Virginia’s growth over the last two years has been concentrated north of the James River, particularly in Northern Virginia and around Richmond, while most of Virginia’s rural counties have lost population, notably in Southside and Southwest Virginia. Similarly, during the 2010s, Northern Virginia accounted for nearly two-thirds of the Commonwealth’s population growth, while every county bordering North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and most counties bordering West Virginia lost population.

Yet, one noticeable difference between the 2020s so far and the last decade is the scale of growth within the Commonwealth. Between 2010 and 2012, Virginia’s population grew by over 185,000 but during the first two years since the 2020 Census, Virginia’s population grew by only 52,000. The slowdown in growth has been primarily due to a shift towards more people moving out of the Commonwealth to other states than moving in. In Northern Virginia, which has contributed to most of Virginia’s out-migration, the fall off in growth has been noticeable. Between 2010 and 2012, the region added 115,000 new residents but since 2020 it has only grown by 23,000. In 2022, the population of Northern Virginia’s older suburbs, concentrated between Arlington and Manassas, where most of Northern Virginians live, was smaller than in 2017.

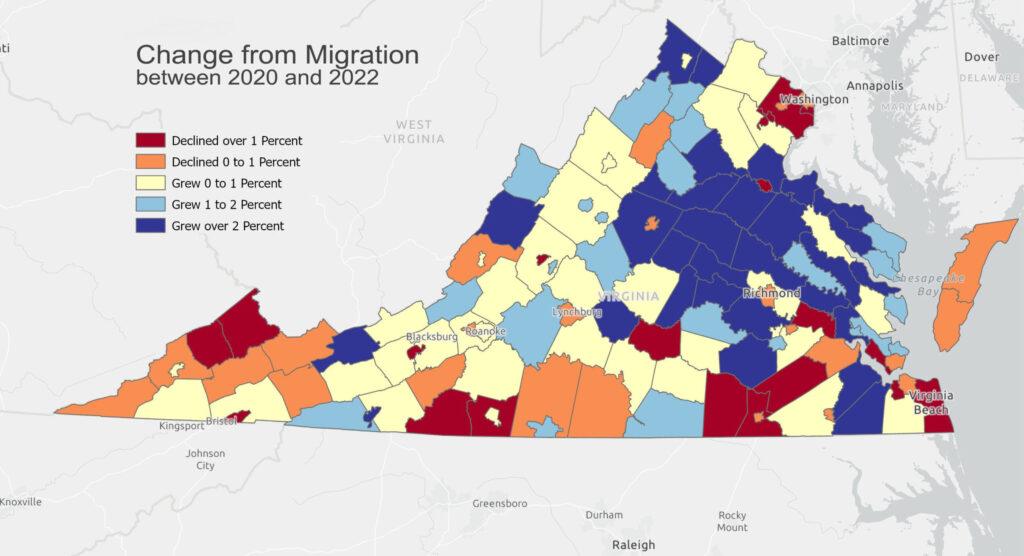

Virginia’s exurbs and Richmond are attracting more Northern Virginians

Many residents who left Northern Virginia moved to the fast-growing metro areas in the South, such as Raleigh or Charlotte, but a large number of movers also stayed in Virginia moving to nearby counties and cities. Migration from Northern Virginia into the Richmond Metro area has risen by nearly 40 percent since the mid-2010s. Richmond has been so attractive to Northern Virginians and residents of other large metro areas that in 2022 Zillow ranked it the second most popular metro area in the country for prospective home buyers, while Bon Air in Chesterfield County was ranked the third most popular zip code by Zillow. As the economy strengthened in the late 2010s, migration into many of Virginia’s small metro areas and rural counties increased, driven in part by people leaving large East Coast urban areas.

In some ways, the demographic trends that Virginia, and much of the country, has experienced in recent years are more similar to those seen during the 2000s housing boom than the trends during most of the past decade. During most of the 2000s, the populations of counties on the edges of metro areas, such as Louisa or Isle of Wight, boomed as they attracted new residents looking for more affordable housing and an improved quality of life. During the same period, in many urban counties, population growth slowed considerably or even shifted into decline, much as it has in Fairfax and Virginia Beach.

An aging population is helping slow population growth

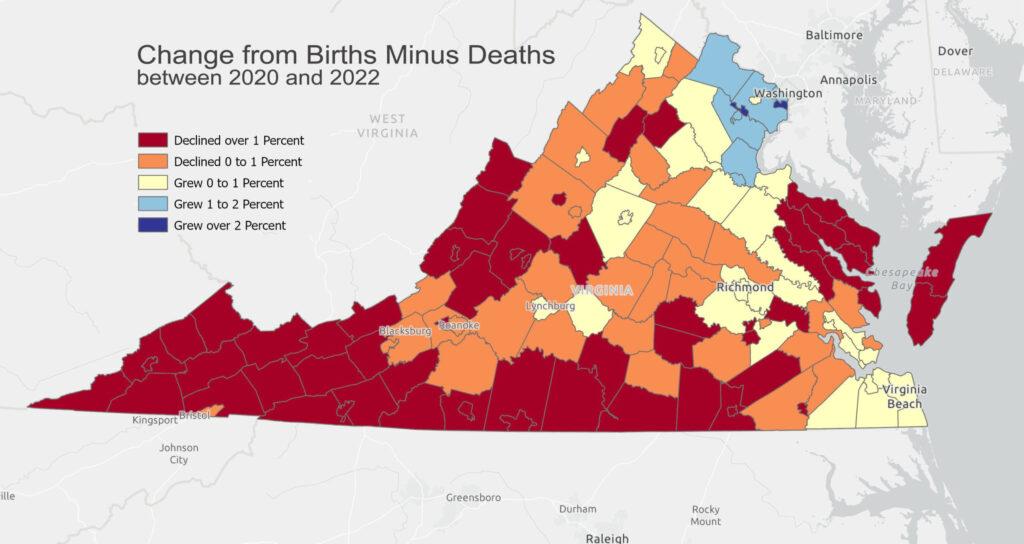

Virginia’s population today is older than it was two decades ago; the median age has risen in every county within the Commonwealth; and in 78 of Virginia’s 95 counties half the population is now older than 40. As a result, the number of deaths in Virginia has risen while birth rates have fallen, helping slow growth and causing the population in most counties to decline during the 2010s. In 2022, nearly 5,000 more people moved to Virginia’s rural communities than left—the largest number since the 2000s housing boom—but Virginia’s rural population still declined because it had over 5,000 more deaths than births.

Future growth in Virginia’s exurbs is unclear

As the pandemic recedes over the next few years and death rates drop, growth may pick up in more of Virginia’s communities. Preliminary CDC data shows fewer deaths in Virginia in 2022 than in 2021. In addition, the number of births is increasing in parts of the Commonwealth. Since 2016, birth rates have risen in 38 of Virginia’s 95 counties, most of them on the edges of metro areas and attractive to young families, such as Louisa where births have risen by 9 percent.

During the housing boom in mid-2000s, most of Virginia’s rural and exurban counties had a similar influx of new residents but after the Great Recession hit in the late 2000s, these counties experienced a decade of slow growth or decline. Given the recent downturn in the housing market and a potential recession looming, another sharp slowdown in growth may appear to be on the horizon for Virginia’s exurbs. Yet there are also some significant differences between today and the 2000s, notably how much more expensive housing is in many of the country’s large urban areas, particularly Northern Virginia. Since 2010, the median home price in Prince William, where many of Louisa’s new residents have moved from, has risen from $34,000 more than in Louisa to nearly $200,000 more last year, in other Northern Virginia counties the median home price is close to $400,000 more. Another difference is how ubiquitous remote work has become, allowing many workers to live further from their employer and helping spur growth in Virginia’s rural and exurban counties. If current patterns continue, Virginia may soon experience trends similar to a time prior to the Great Recession with exurban counties struggling to keep up with population growth and some cities struggling to cope with a declining population and tax base.