The U.S. Birth Rate is near an all-time low, and that may not be a bad thing

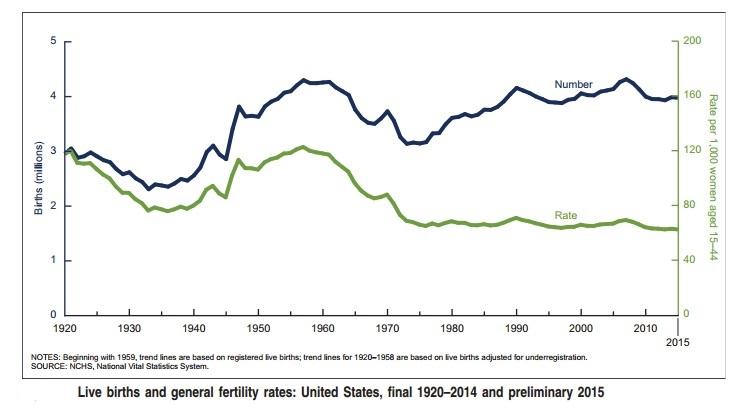

In June, the National Center for Health Statistics released the total number of births in the U.S. during 2015. Given that the economy has been growing for six years since the recession ended in 2009, most economists were expecting the number of births to increase. However, there were actually fewer births in 2015 than in 2014 with the U.S fertility rate (the number of births per 1000 women ages 15 to 44) reaching an all-time low.

Altogether there have been 3.4 million fewer births since 2007 than would have been expected if pre-recession fertility rates had not declined. The continuing decline in births has caused economists to worry about its long term impact on society and the economy. Recently, the Census Bureau cut its 2008 projection of the U.S. population in 2050 from 439 million to 398 million, in part because of lower fertility rates. The Social Security Administration has also warned that the decline in births could cause the size of the social security deficit to double because there will be fewer workers to support the rapidly growing retiree population.

The 16 and pregnant effect

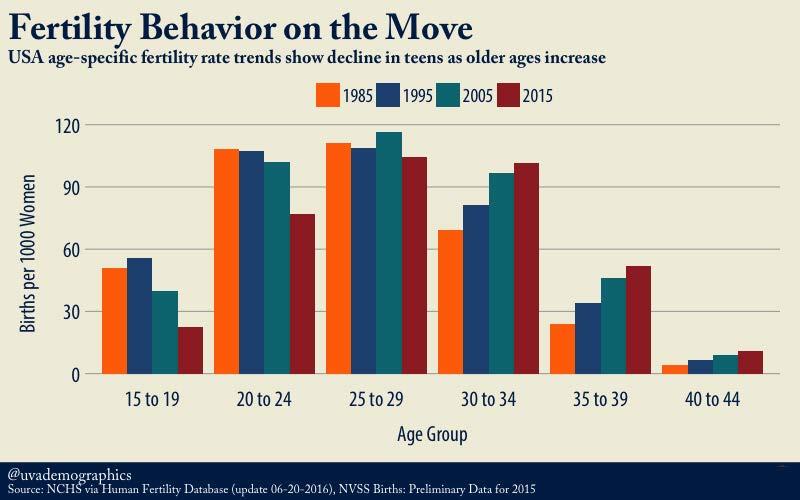

While lower fertility rates will undoubtedly have an impact on society and the economy, it’s important to understand why births are still declining six years after the recession ended. Initially, during the recession, the decline in births was concentrated among mothers 20 years and older, though births decreased considerably among teenagers as well. Since the recession ended, the number of births among mothers 20 years and older has begun to increase again, particularly among mothers over 30, but the number of teen births has continued to decline since 2009. Overall, the number of births in the U.S. declined by 339,374 between 2007 and 2015, but the decline in teenage births accounted for 218,872 or two-thirds of the total decline in U.S. births.

After drugs and crime, teenage pregnancies have been perhaps the largest target of social campaigns in recent decades. Teenage pregnancy was once fairly common and even socially acceptable, particularly after World War II, when there were plenty of well-paying jobs available that did not require a high school diploma, much less a college degree. As these low-skill jobs began to disappear, the teenage birth rate started to fall. By the mid-2000s the U.S. teen birth rate had declined by 50 percent since 1960.

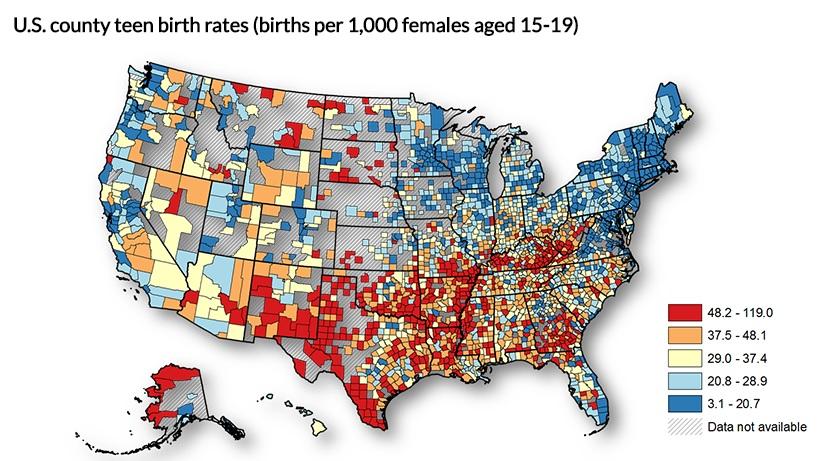

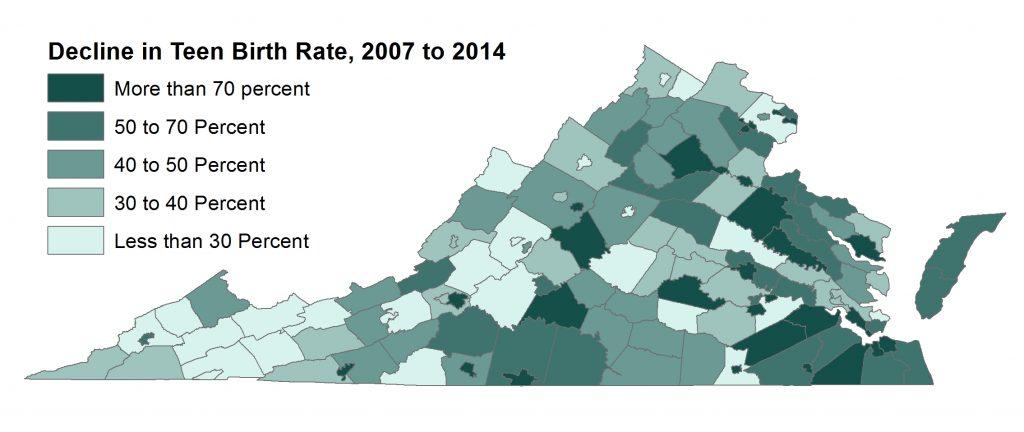

Yet in areas of the country where low skill jobs are still prevalent, such as in the Mississippi Delta, the Appalachian Coalfields and some inner cities, teen birth rates remained largely unchanged during recent decades. But the past recession was particularly hard on areas with high concentrations of low skilled workers, making supporting a family without a high school or college diploma even more difficult. The result has been that these rural and urban areas contributed to a disproportionate share of the over 50 percent decline in the teen birth rate since 2007. In the City of Richmond, Virginia, just between 2007 and 2014, the number of teen births fell from 470 to 149.

Not cancelled but postponed

Often, many of the same localities that experienced the largest declines in their teen birth rate also had the largest increases in their high school graduation rates. Nationally, the decline in teen births has coincided with a significant rise in high school graduation rates, as well as an increase in college attendance rates. This suggests that more teenagers are putting off starting families until they have earned a high school and maybe a college degree.

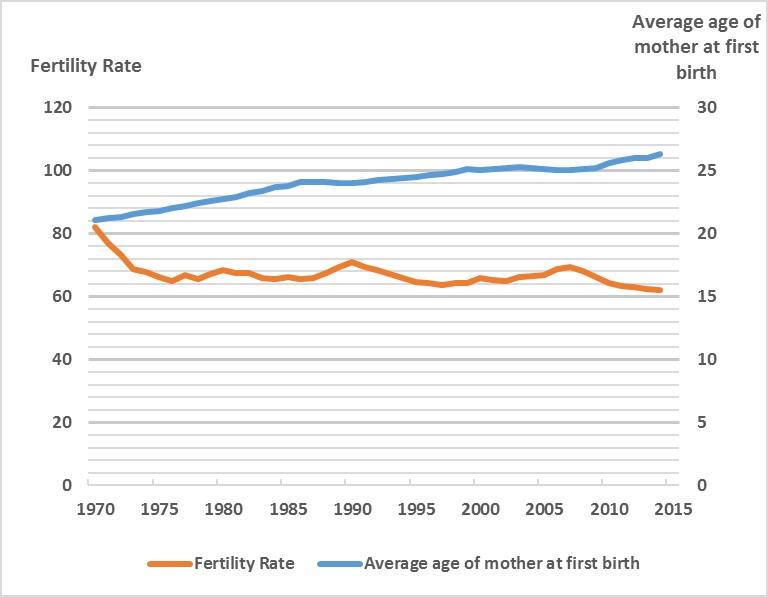

So fears of a “baby bust” may be somewhat misplaced; most of the decline in births since 2007 has been among teenagers who are likely putting off starting families, often to further their education and training. In the 1970s and early 1980s, fertility rates also declined as couples delayed starting families, but this was followed by the “echo baby boom” during the late 1980s and early 1990s when most millennials were born. This pattern repeated itself during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Now that more couples are again putting off starting families it appears the U.S. is experiencing a repeat of the fertility pattern.

Expecting a large baby boom, however, might also be too optimistic. A common theory in demography is that fertility delayed is often fertility foregone. The chart above somewhat supports that idea; as couples in recent decades have steadily waited longer before starting families, fertility rates have overall trended downwards slightly. Putting off starting a family narrows the time frame when a couple can have children, and many couples have chosen to have smaller families than their parents’ generation.

If the decision by many teenagers and young adults to delay starting families causes fertility rates to continue to decline, it will have wide reaching economic effects, notably by shrinking the potential size of the labor force. But there are also potential positive effects from the decline in teen fertility rates—namely putting off starting a family allows teens to further their education and training which should, in turn, boost their productivity and earnings, making it easier for them to support themselves and their family. With the prospect of further automation of low skill jobs and the persistent demand for skilled workers, the decline in U.S. fertility rates may have more of a positive effect on the labor force than it might initially appear.