Crime and Police Data in Virginia

An always contentious topic, crime and policing have been at the forefront of American life for the past few years, and even more so in 2020. While there is no comprehensive record of every incident that may have occurred, in the broader context of criminal justice reform, national- and state-level crime data do tell an interesting story. Crime rates differ over space and time, and depend on several factors, including—but not limited to—population size and composition, degree of urbanization, economic well-being (income, poverty, employment levels), weather conditions, geographical terrain, citizen’s reporting practices, and the influence of law enforcement agencies, to name a few. For now, we focus on population size, density, urban-rural differences, and type of crime, to understand the trends in crime statistics across different jurisdictions in Virginia. We also take a brief look at the incidence of hate crimes reported within the Commonwealth, which further demonstrates the complexities of crime and policing data. Finally, we try to examine the police presence in Virginia by comparing the distribution of law enforcement officers across localities.

MAJOR CRIMES ACROSS LOCALITIES

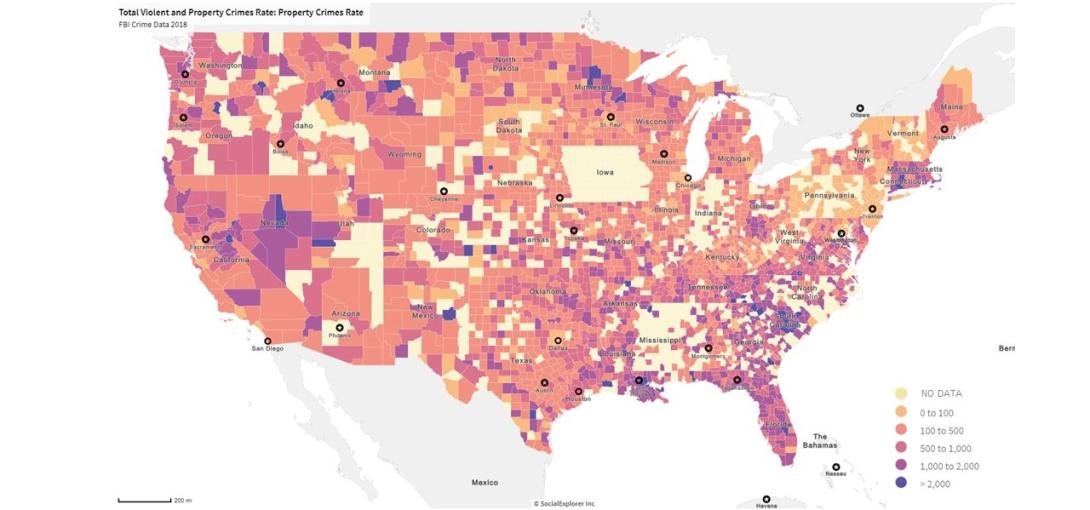

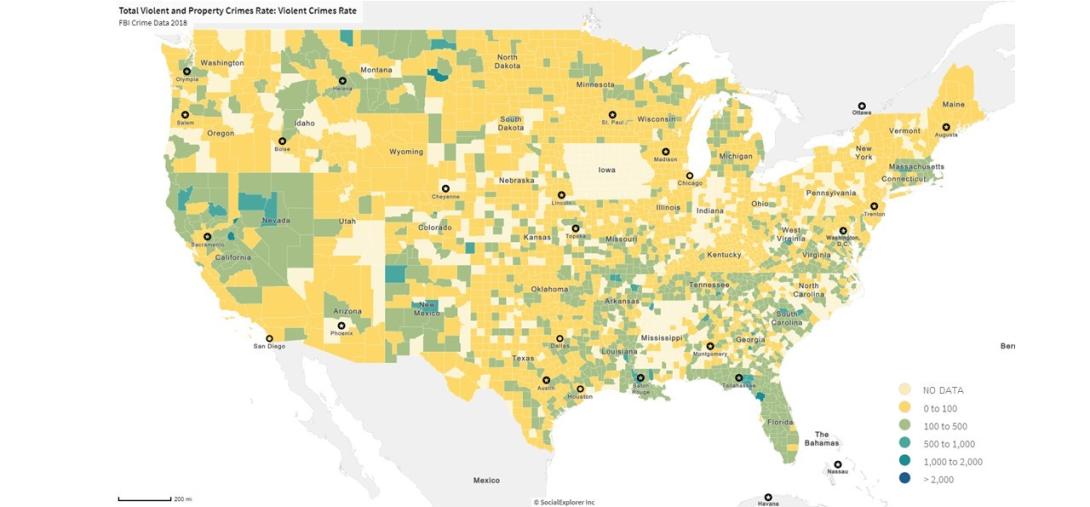

In tandem with the national trend, Virginia has experienced a decline in property and violent crime rates over the last decade. Compared to the other states or counties across the U.S., Virginia and its 133 localities are not outliers, as evident from the maps below using FBI Crime Data1. In 2018, Virginia’s property crime rate was 1665.8 per 100,000, compared to the national rate of 2199.5. The violent crime rate in that same year was 380.6 per 100,000 in the U.S., while in Virginia the rate was 200 per 100,0002.

In Virginia, one incident of criminal activity was reported every 1 minute and 24 seconds in 2019. The average frequency for property crimes was higher than crimes against persons or society. What is considered a crime vs. an offense vs. an incident is not mutually exclusive and for those interested, a detailed definition is available on page four of the VSP Crime in Virginia 2019 report.

Contextualizing the crime statistics with demographic data highlights the variation within the Commonwealth. Since areas with larger populations often are more likely to experience a higher volume of crime, we construct a standardized rate of crime per 100,000 population. So if we compare localities just by number of crimes, then the top 10 are all high density population centers of larger metro areas (such as Fairfax county, Virginia Beach city, or Chesterfield County), whereas if we rank the top 10 localities with the highest crime rates, then the list changes to smaller independent cities such as Roanoke, Portsmouth, Galax, and Colonial Heights. These correlations between population and overall crime also apply when incidents are broken down by the specific type of crime against person/property/society3, as seen in the map below.

HATE CRIMES

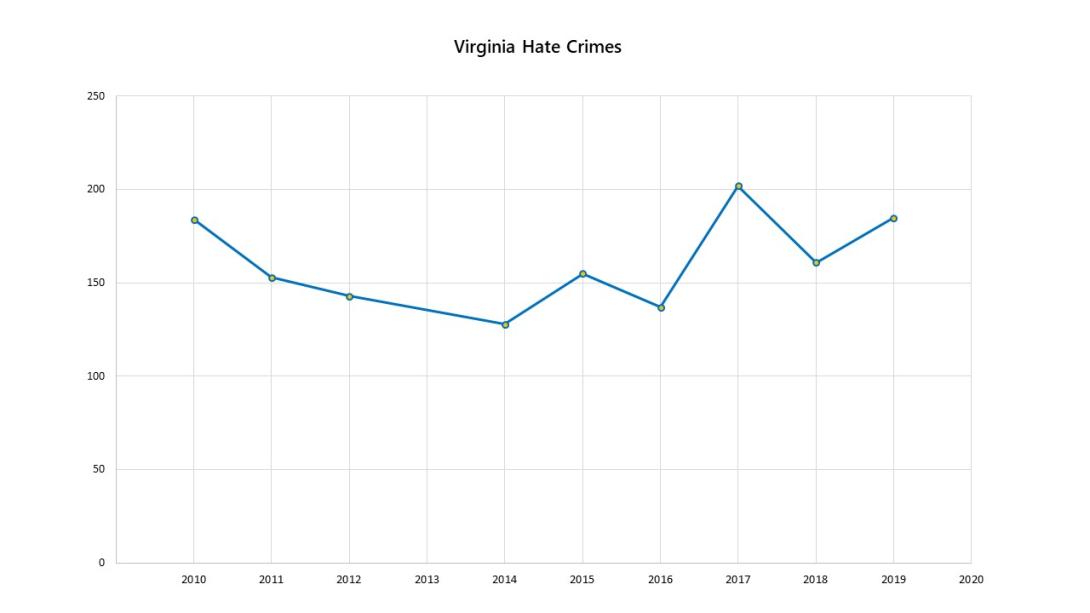

While most other types of crime have seen a decline, hate crimes have increased as of late. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) defines a hate crime as “a crime motivated by bias against race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability.” They distinguish a hate crime from a bias or hate incident as the former involves property damage, threats, and/or violence in addition to bias. The DOJ notes that an estimated 250,000 hate crimes were committed annually across the U.S. from 2004-2015, with a large portion of the crimes not being reported. This adds a layer of difficulty in obtaining reliable crime data, since a crime must be reported for it to be counted. Additionally, this prevents policy makers and government officials from being able to work on bills and initiatives to fight hate crimes when they aren’t aware of the extent or specific nature of bias for these crimes.

In 2017, 202 hate crimes were reported in Virginia. This number dropped to 161 in 2018 but rose again to 185 in 2019, with an uptick of 15%. Hate crimes based on sexual orientation saw the biggest increase of 43% (from 23 to 33 offenses), followed by race hate crimes which rose by 23% (from 97 to 119). Over the same time period, anti-Hispanic or Latino hate crimes increased while hate crimes against a person with a disability declined4.

Hate crime reporting fluctuates based on the political climate, and the legal definitions used, which can change over time. The current Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring is attempting to address these issues by updating Virginia’s definition of hate crimes, which will allow stricter prosecution and hopefully deter people from committing such criminal acts, while simultaneously helping victims feel more comfortable to report every incident.

POLICE DISTRIBUTION ACROSS LOCALITIES

With the ongoing national conversation on presence of police and their role in serving the public, we also looked at the data to see how the police force is distributed across Virginia. Full-time law enforcement employees (24,385 in Virginia), including officers (19,393) and civilians (4,992), may belong to a broad range of agencies, such as the city/county local police force, state police, or college/university security divisions5. Additionally, some jurisdictions may have both sheriffs’ offices and police departments.

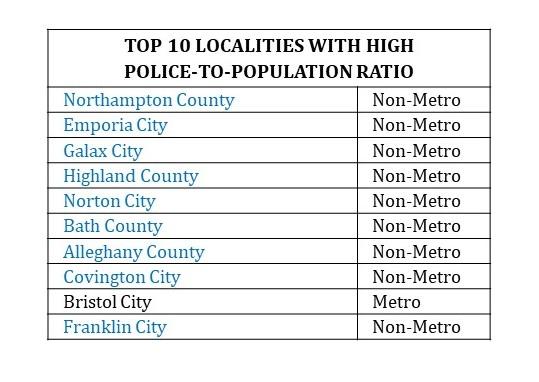

As per the Virginia State Police 2019 report, there is 1 sworn full-time law enforcement officer for every 440 people in Virginia. But the size of the police force varies across localities, and officers are not uniformly distributed with respect to population size or geographic area. Using the size of law enforcement agencies and locality’s population and area, we calculated ratios of police to the population (cop-to-pop ratio) and of police to the locality’s area (cop-to-area).

At first glance, it seems curious that 9 out of the top 10 localities with high police-to-population ratios are actually rural or non-metro areas, but taking into account Virginia’s topography and density makes this more plausible. Certain localities with rugged terrain have a smaller population spread across a larger territory, resulting in longer travel times to respond to calls. Hence the corresponding number of officers required to serve the citizens may seem larger in proportion but be a practical necessity to meet local needs in a timely manner.

This is true in sparsely inhabited counties like Bath (5 people per square mile) and Highland (8 people per square mile) in the Valley, where each officer may serve between 170 to 200 residents, but must cover over 25 to 30 square miles. On the other end of the spectrum, in densely populated areas like Alexandria, the cop-to-pop ratio is low while the ratio of cop-to-area is high. This means that while each officer serves a greater number of people (over a 1000 people per police officer), they cover far less physical area (about 15 square miles). Similarly, the top 10 localities that have the highest cop-to-area concentration are all metro areas with many having much smaller geographies, such as Falls Church city and Manassas Park city, each covering only 2 or 3 square miles.

The Virginia State Police’s Crime in Virginia 2019 report is available here.

SOURCE NOTES:

1: FBI Crime Data for US and 50 states (2018) from Social Explorer.

2: FBI’s Crime Data Explorer.

3: Virginia locality level data on crimes against person/property/society (2019) from the online portal.

4: From Pg 59 of Crime in Virginia 2019 and Pg 53 of Crime in Virginia 2018 report.

5: From Pg 80 of Crime in Virginia 2019.