Could the “two-body problem” be contributing to rural brain drain?

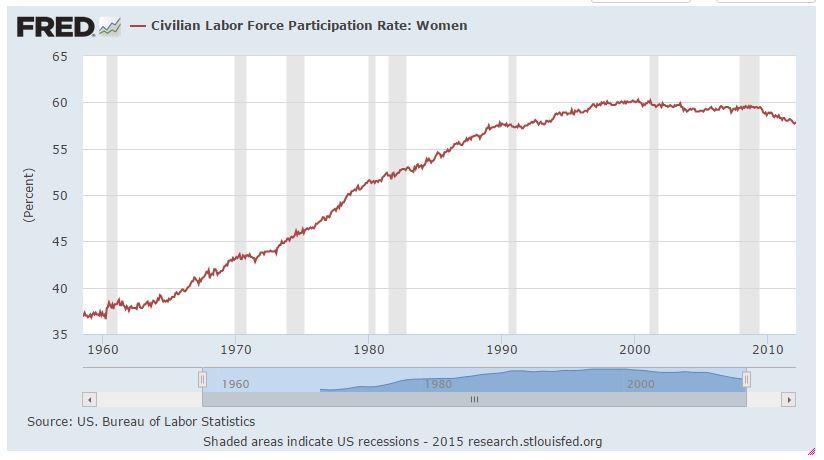

More career women means more two-career couples

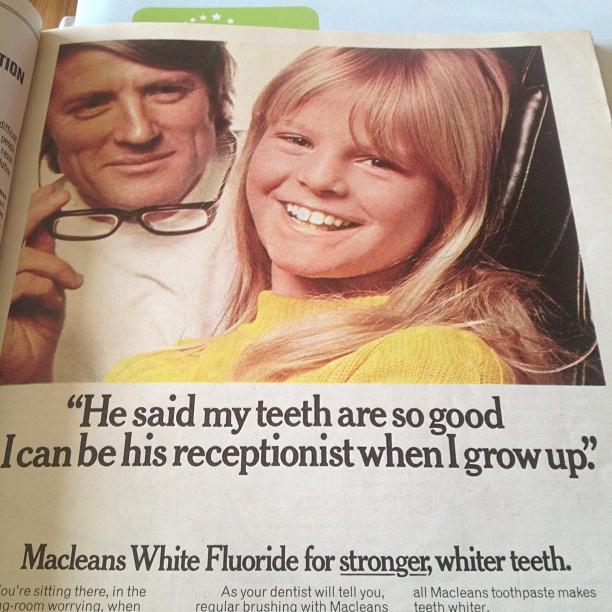

One of the biggest economic stories of the last half-century has been the growing participation of women in the workforce. And it’s not just the number of women working that’s important; it’s the type of work they are doing. We’ve moved rapidly from a time when a working woman’s options were: “teacher, nurse, or secretary” to a time when more women are getting advanced degrees in a full spectrum of specialized fields.

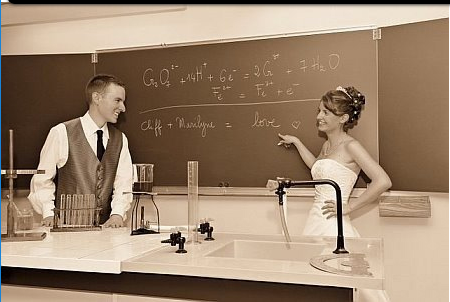

At the same time – and not unrelatedly – people are increasingly likely to marry someone with a comparable level of education. Consider how common it is for physicians to pair off with other physicians, engineers to marry lawyers, computer programmers to join romantic forces with data analysts, and for academics to [wedding] band together. The end result is that educated couples tend to have two expert, specialized skill sets to bring to the labor force.

Research suggests that couples are more likely to privilege a male partner’s job when choosing a place to live, a phenomenon that many have chalked up to traditional social norms, expectations about child-rearing, or sexism. However, a recent study by demographer Alan Benson found that it was simply a result of men’s concentration in more specialized (and geographically clustered) careers, compared with women’s historical participation in less specialized “support” jobs or geographically flexible fields like teaching and healthcare. In fact, when controlling for occupation, couples are just as likely to move for the woman’s job. Given Americans’ notorious willingness to move across the country for work (Alexis de Tocqueville noted this all the way back in the 1830’s), many highly-educated couples face tough choices about geography as they try to juggle two specialized careers that are – very literally – going in different directions.

The two-body problem

Academia is the best place to watch this play out, both because of its hyper-specialization and the dramatic gains made by women over the past few decades. As might be expected after spending years cooped up in graduate schools, PhD’s are disproportionately likely to have relationships with other PhD’s. Unfortunately for them, tenure track jobs are scarce, highly specialized, and often located in isolated college towns, making it difficult for both partners to find work in the same place. This story is so common that graduate students already have a name for it: the “two-body problem,” a pun on the three-body problem in classical mechanics. Universities across the country are developing programs and hiring policies to try to address the issue, which is putting small colleges in rural areas at a significant disadvantage in attracting talented academics. The US Foreign Service has similarly had to develop programs to provide job options for the career-oriented “trailing spouses” of qualified diplomats.

Academia is an extreme example, but the two-body problem may be making its way into other fields as the number of women engineers, executives, doctors, and lawyers continues to climb. And if that’s the case, it could be part of why it’s so difficult to attract knowledge economy jobs to smaller cities and rural areas.

A look at the data

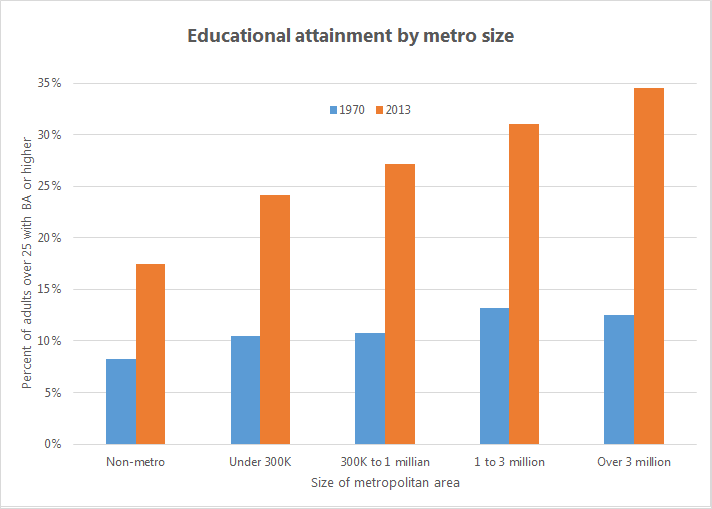

Larger metropolitan areas have more jobs to attract degree-holders, so we would expect there to be more college graduates there, whether married to another graduate or not. The number of college degree holders has grown everywhere, but college graduates have clearly shifted heavily towards larger metropolitan areas. There are plenty of reasons why high-skill jobs cluster together in large cities. In planning, we call these “agglomeration economies,” and they allow firms to benefit from the presence of other similar firms and to hire from the same talent pool.

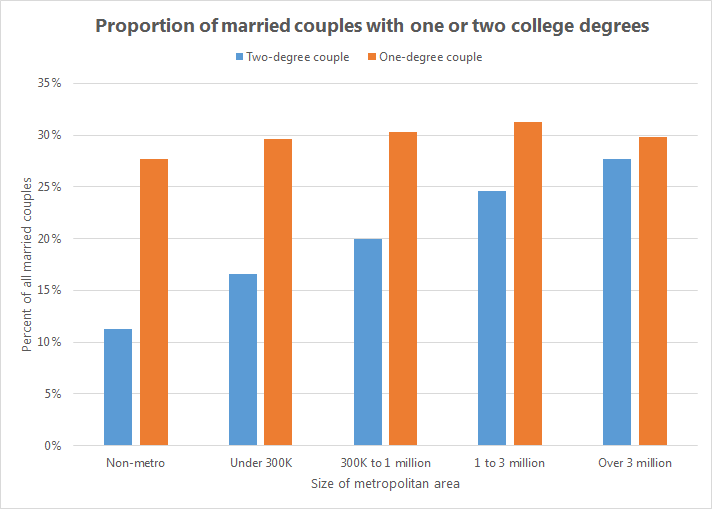

If the two-body problem is a real factor influencing couples’ decisions about where to live – and if the common outcome is a compromise move to an area that will meet both partners’ needs – then we would expect married couples with two degrees to favor larger metro areas, and couples with only one degree to hold a relatively larger share of degree-requiring jobs in smaller metros than in larger metros. In fact, this is exactly what we see:

While by no means proof-positive that the two-body problem is as much of a concern for small metros and rural towns as it is for the couples trying to find work near each other, these trends could indicate that larger metropolitan areas have a significant competitive advantage in attracting high-paying knowledge economy jobs. While larger metros lumber on and continue to add college grads despite regional economic problems, rural areas and small towns struggle to find ways to hang onto their college graduates. This makes sense in a world where college graduates are more likely to marry college graduates and both expect to find work in their field.

What this means for cities

The implications for local economic development are significant, especially in smaller cities and towns. Smaller cities that want to grow their economies by increasing the number of skilled jobs – and thereby attract more highly-skilled workers – should think regionally, because the broader area’s ability to provide options for workers’ spouses may increase couples’ willingness to move there.

Moreover, small cities – and their broader regions – should consider how best to support creative work arrangements. Today a growing number of couples are living and working apart because of separate careers. Others have resorted to telecommuting, which Joseph Kane of the Brookings Institute notes is on the rise everywhere. Kane’s discussion focused on transportation-related causes, but two-career couples might be an even bigger reason. The leading metro areas for telecommuting are small cities with major universities, ground zero for the two-body problem. Supporting broadband internet and shared workspaces could help make cities more hospitable to the spouses of the skilled laborers they are trying to attract.