Will Covid-19 accelerate the growth in homeschooling in Virginia?

While COVID-19 has impacted and continues to impact communities worldwide, it is also changing, in perhaps sometimes positive ways, how we manage our daily lives. The pandemic has caused many of us to rely much more heavily on online services that allow us to work, shop and even have doctor’s appointments from home. It has also required many parents who have school-age children to jump head first into the world of home schooling while also managing their own work schedules. Despite the difficulties that come with the shift in the way we work, learn and live, it is likely that we will continue to adopt a more technology-reliant and home-based lifestyle even after the pandemic. And this is particularly true with homeschooling, which will inevitably remain more commonplace after the pandemic than it was before it.

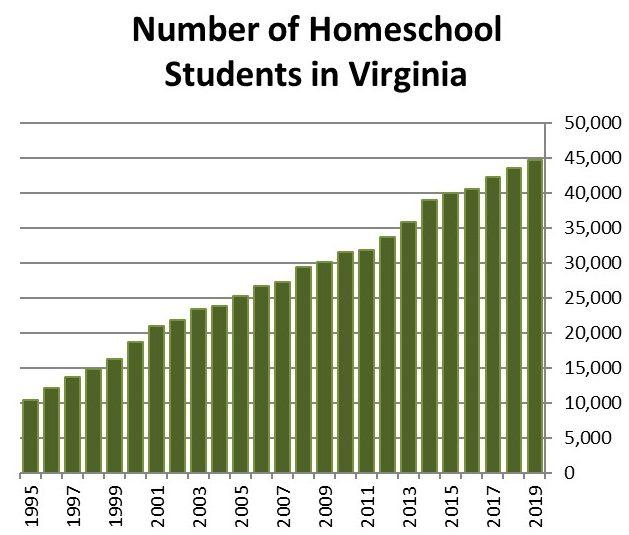

Before the pandemic, the number of children being privately educated at home was increasing much faster in Virginia and the U.S. as a whole than student enrollment in public or private schools. Nationally, the number of children educated at home nearly doubled over the last twenty years. Despite a declining school-age population in most of Virginia, the number of homeschooled students has grown even more quickly throughout the Commonwealth, reaching close to 45,000 in 2019. If homeschoolers in Virginia made up a school division, it would be the fastest growing division, expanding by 48 percent in the last ten years, and seventh largest of Virginia’s 133 school divisions.

Percent of K-12 Students Homeschooled in 2019

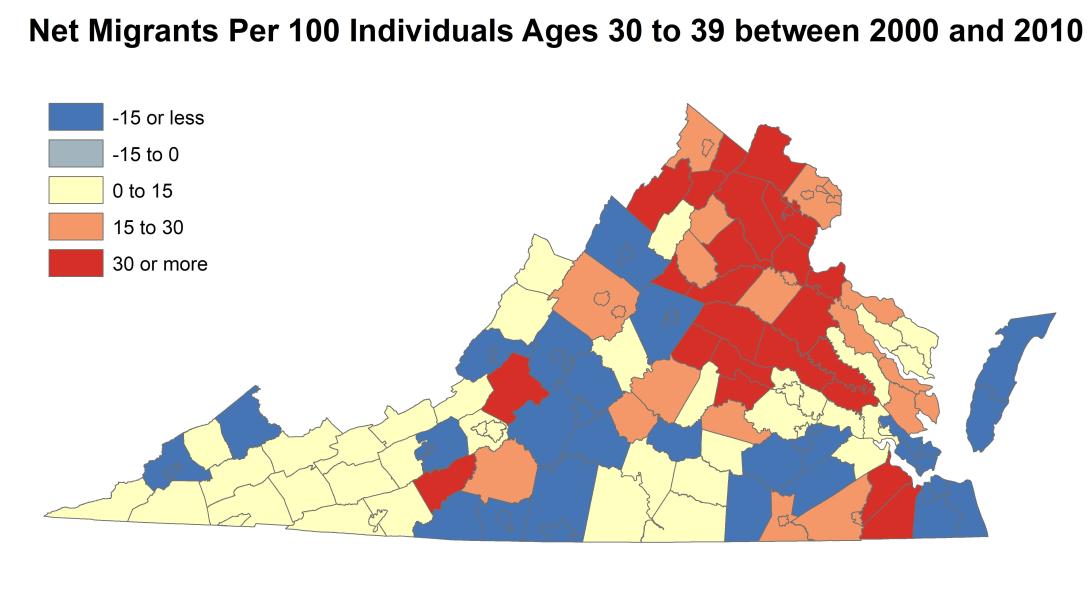

Though the share of children who are homeschooled has steadily risen across Virginia, the highest homeschooling rates in Virginia are concentrated in its exurban counties along the edges of metro areas. These same counties typically attract a disproportionate number of young families from Virginia’s urban and suburban areas. In Floyd County, which borders the Blacksburg and Roanoke metro areas, the county’s total population rose by 10 percent between 2000 and 2010. While total growth was slower than Virginia as a whole, the population between ages 30 and 39 grew by a third as a result of young adults and families moving to the county. Today Floyd County has one of the highest homeschooling rates in Virginia, at 13 percent.

In Virginia and other states, homeschooling is typically more common in localities with above-average telecommuting rates. Among the ten Virginia localities with the highest rates of telecommuting, the share of children who are homeschooled is double the statewide rate. In the Asheville, North Carolina Metro Area, which has the fifth highest rate of telecommuting among U.S. metro areas, over 13 percent of children were homeschooled in 2019, compared to 3 percent in Virginia. In some counties on the edges of the Asheville Metro Area, the rates were even higher—between a fifth and a quarter of children were homeschooled. The typically higher rates of homeschooling found in localities that also have high telecommuting rates may be due, in part, to the increased flexibility telecommuting parents have in their work schedules.

Who is more likely to homeschool?

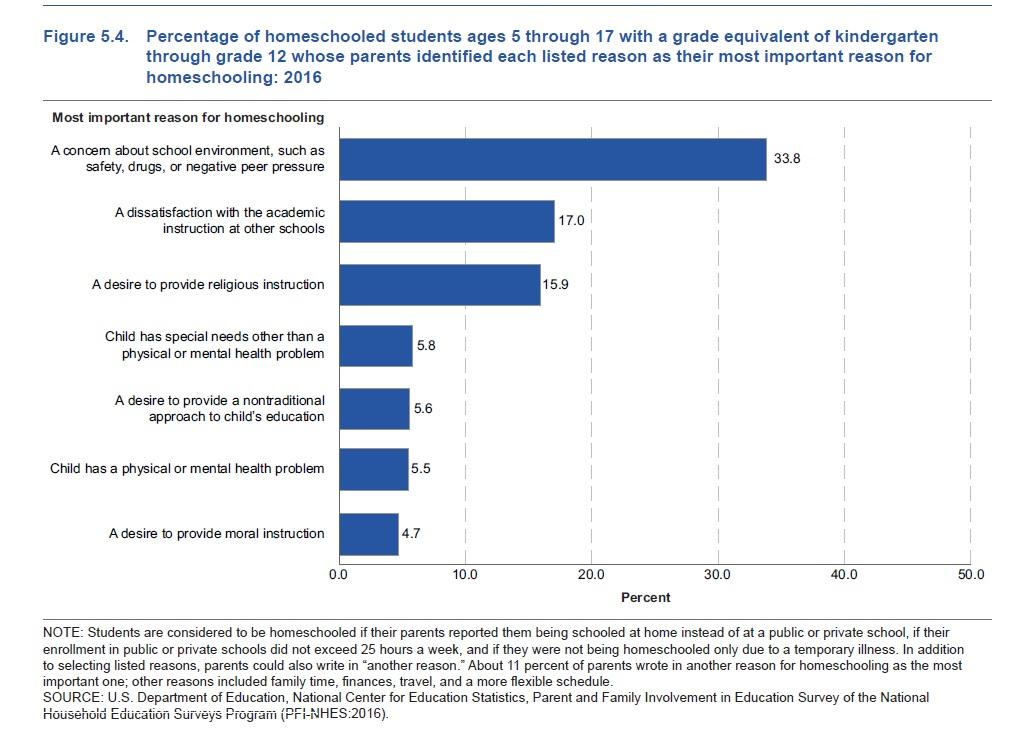

As the number of students educated at home has risen in Virginia and across the U.S., national surveys conducted by the Department of Education show that parents who homeschool increasingly come from a wide variety of backgrounds. Only a small majority of homeschooled students live in a household with one parent in the labor force and one parent not in the labor force. Most of the remaining homeschooled students live with two parents who both work or with a single parent who works. The number of homeschoolers who are Hispanic has grown nearly six-fold since 1999, and today homeschoolers are disproportionately likely to be Hispanic. Parents who homeschool also have varying educational backgrounds, with the majority either having a bachelor’s degree or a high school degree or less. According to the national survey, the top three reasons parents decided to homeschool included: 1) concerns about the environment in school (34 percent), 2) dissatisfaction with academic instruction in school (17 percent), and 3) a desire to provide religious instruction (16 percent).

Within Virginia, the diverse reasons parents choose to homeschool is reflected in its different localities. For example, the Lynchburg metro area has a homeschooling rate nearly double Virginia’s rate, in part, due to the region’s substantial congregation of evangelical Protestants who are more likely to homeschool their children. In Floyd County, to the west of Lynchburg, the high rate of homeschooling is, to some degree, due to the heavy influence of its communes who also helped kick start the modern homeschool movement in Virginia.

What is the future of homeschooling?

Growth in homeschooling is being driven by parents who increasingly come from a wide range of backgrounds and who choose to homeschool for a variety of reasons, which indicates that the demographic constraints on how much further homeschooling can grow are looser than they might appear and possibly that a fundamental cultural shift is taking place. Prior to the pandemic, Milton Gaither, who studies the history of education at Messiah College, observed that the best way to make sense of the explosive growth in homeschooling is to recognize that it is part of “a larger renegotiation of the accepted boundaries between public and private, personal and institutional.” This can been seen in the growing popularity (even before the pandemic) of other home-based trends, such as working from home, home-based healthcare, and even home birthing.

Certainly, in 2020 most Americans have had to renegotiate the boundaries between their public and private lives as they have adapted to the pandemic. When the pandemic is over, it appears likely that the boundaries between public and private life will not return to past norms. Telecommuting, which was already growing rapidly in Virginia, has been boosted substantially by the pandemic, with many employers planning to continue offering telecommuting as an option in the future.

What long-term effects the pandemic will have on education remain to be seen, but so far, the shift for many to a more technology-reliant and home-based lifestyle has helped create social conditions more conducive to homeschooling. If Milton Gaither is correct, the future growth of telecommuting is likely to occur in synchrony with the growth of homeschooling and other home-based activities.

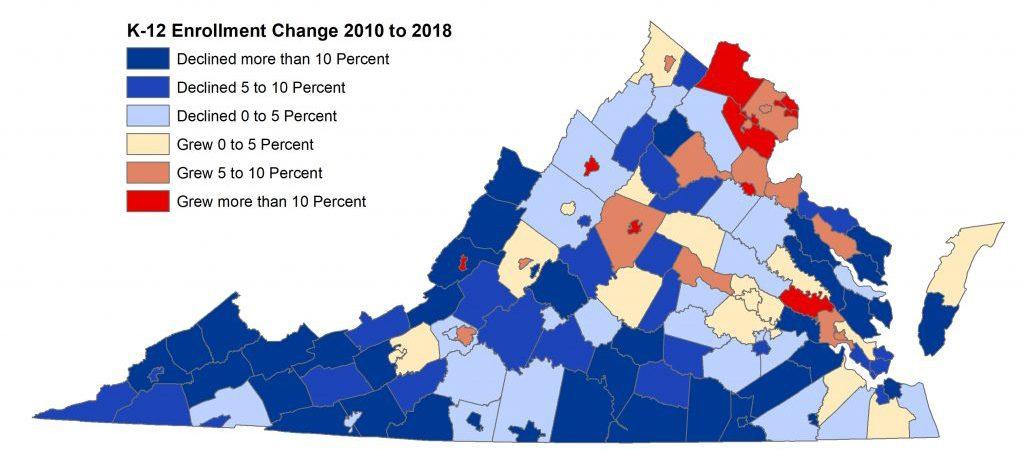

For most of Virginia’s communities homeschooling rates are rising even as the number of students in their public schools is declining, in some cases rapidly. Over the last ten years, public school enrollment outside Virginia’s three largest metro areas—Hampton Roads, Northern Virginia and Richmond—has declined collectively by over 13,000 students. In 15 of Virginia’s rural school divisions public school enrolment has declined by over 20 percent in the last ten years. During the same period, the number of homeschoolers outside Virginia’s three largest metro areas has risen by nearly 6,000.

Shrinking enrollment typically means localities will receive less state education funding, but the decline in enrollment may also affect communities in a less quantifiable but more fundamental way. The term “social capitol” was coined a century ago by a West Virginia school administrator named L.J. Hanifan to describe how fundamental schools were in supporting the networks and shared values that enabled social co-operation in the communities he worked in. Given that school divisions are both the largest employer and an anchoring institution in most of Virginia’s counties and cities, the decline in divisions’ enrollment and employment is a change that has the potential to increase social fragmentation in communities.

Many public schools have tried to adapt to the decline in their student enrollments and the growth in homeschooling by being more inclusive to homeschoolers in their community. In Virginia, about half of school divisions now permit homeschoolers to enroll in classes part-time, while the Virginia Department of Education allows homeschooled students to enroll in its Virtual Virginia program for a fee. Outside of Virginia, most states now allow homeschoolers to participate in public school varsity sports. As homeschooling has grown more common in recent decades, some of the differences between education at home and in public or private schools have become less distinct. If virtual education remains common after the pandemic, those differences may become even less distinct.

Whether the percentage of K-12 students in Virginia who are privately homeschooled will eventually reach the double-digit levels seen in Asheville and some Virginia counties is difficult to predict. Despite the almost certain acceleration in the growth of homeschooling as a result of the pandemic, switching to homeschooling is typically a much more difficult change for parents than working from home. Yet each year prior to the pandemic, thousands of Virginians were switching to homeschooling despite its challenges. As radical as have been many of the social changes the pandemic has caused, an acceleration in the growth of homeschooling would arguably be the most radical change of all.