Richmond’s quiet transformation

During most of the 20th century, the neighborhoods where people lived and worked in Richmond — even the boundaries of the city — were shaped by race. For decades after WWII, the city’s leaders fought a well-publicized battle to maintain this system and prevent the city’s population from becoming majority black. In recent years, Richmond has experienced its most significant demographic transformation since the post-war era, but this time the change has occurred much more quietly. Why?

History is a nightmare

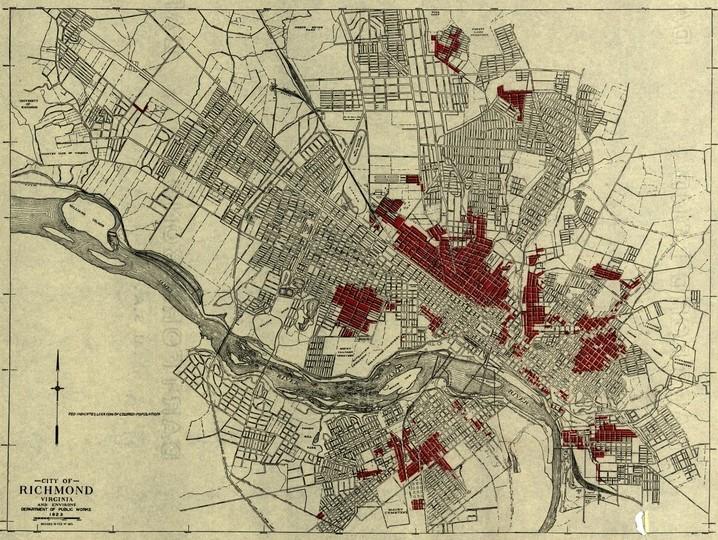

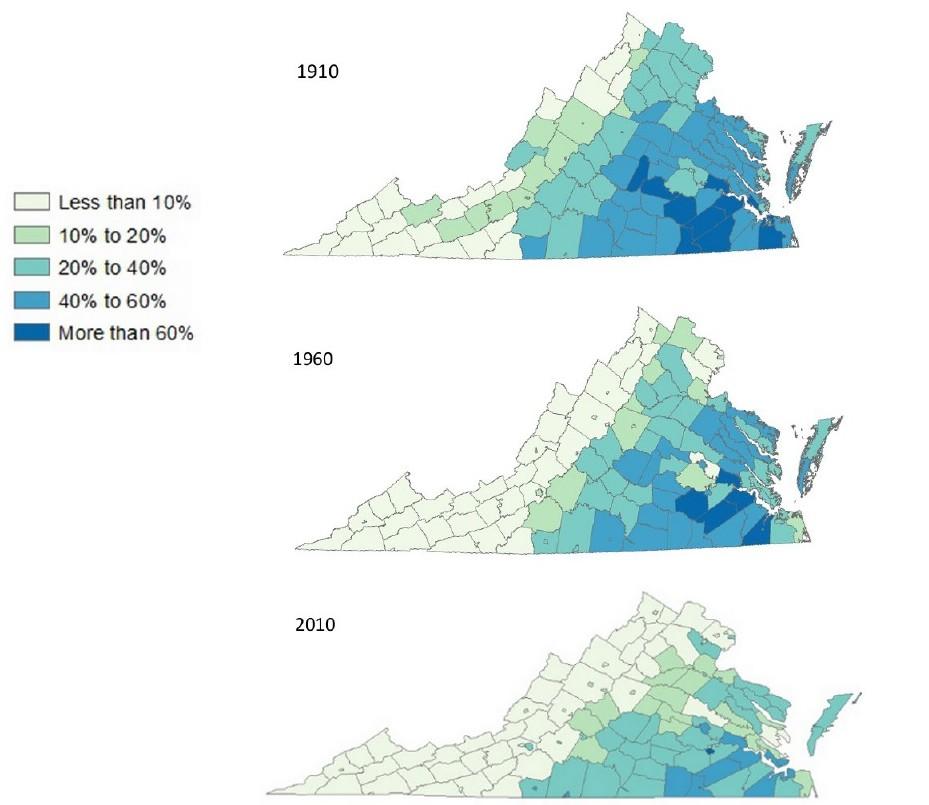

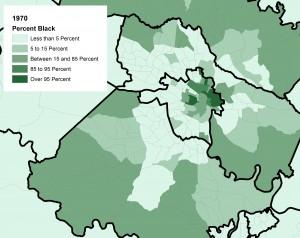

Though Richmond has had a significant black population for much of its history, until the end of World War II, blacks usually made up around one third of the city’s population, with most black residents segregated into the blocks immediately north of Broad Street. During the early 20th century, many blacks in Virginia began moving north out of rural counties to escape grinding poverty and a host of Jim Crow laws which discriminated against them. Initially, many blacks moved to northern cities where better jobs were available, and they hoped discrimination would be less persistent. But Richmond grew increasingly attractive after World War II when for a span of years it had the fastest growing economy in the country.

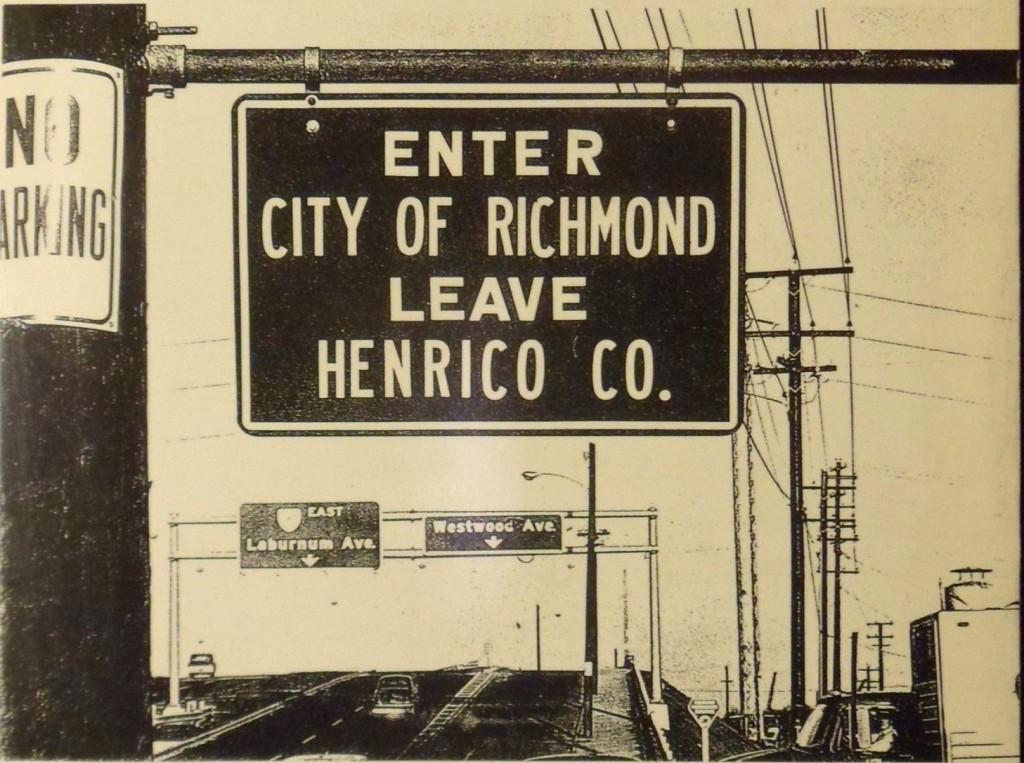

As more blacks moved into Richmond from Virginia’s counties, more white residents moved out of city. The construction of freeways through primarily black neighborhoods only fueled this trend as it allowed more white residents to move out of the city and easily commute back in for work, while the displaced black residents often moved into formerly white neighborhoods. Some neighborhoods, such as around Church Hill, changed from 75 percent white to 95 percent black between 1950 and 1960.

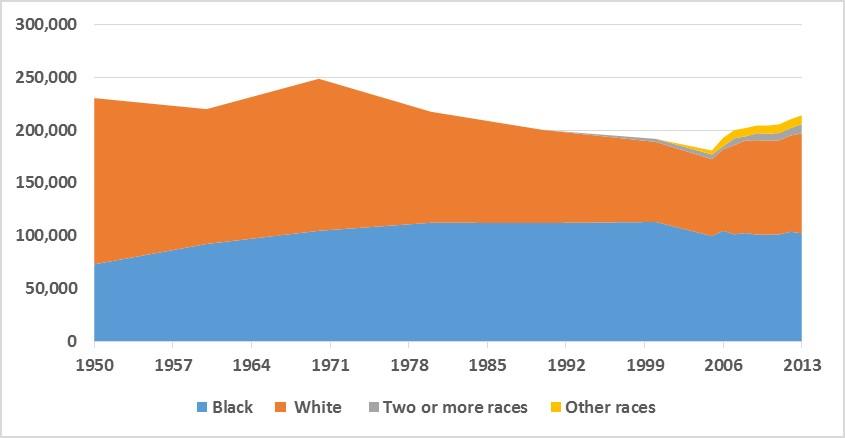

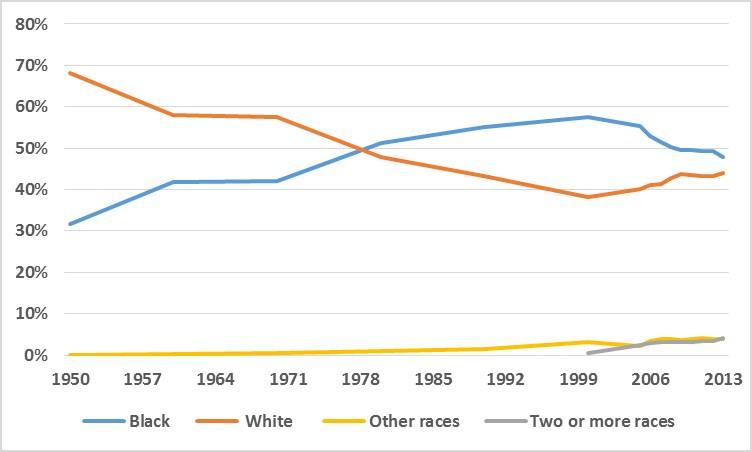

By 1960, Richmond’s population had begun to decline as whites left the city en-masse for the suburbs but the city’s black population continued to grow, increasing to 42 percent of the population. In a period when most Jim Crow laws remained in effect, the prospect of soon having a majority black city was alarming to Richmond’s leaders. To diminish blacks’ voting power, Richmond filed to annex predominantly white suburbs in neighboring counties and to change its city council to an at-large system.

Though Richmond’s annexations were heavily contested, the Supreme Court eventually ruled that the annexations were more motivated by the need to stop the city’s population decline than to dilute the votes of Richmond’s black population. Despite the annexation, by 1977 Richmond’s population was majority black and the city elected its first black mayor.

During the 1980s, many of Richmond’s black residents also began moving out of the city to neighboring counties looking for newer housing, safer neighborhoods and better schools. With both its white and black residents leaving the city, Richmond’s population declined by over 20 percent from around 250,000 in 1970 to 194,000 in the mid-2000s.

The end of history

Since its population bottomed out in the mid-2000s, Richmond has quickly rebounded with its population growing to over 213,000 last year. New construction in Richmond has tripled from levels in the early 2000s. During the past few years, there have been as many new homes built in Richmond as in neighboring counties.

As was the case during the last significant change in Richmond’s population, white migration has fueled much of the trend. However, this time the migration has been into the city, with Richmond’s white population increasing by 30 percent since 2005. Richmond’s black population has also began growing again since the mid-2000s, but much more slowly. The result of this change in trends has been that sometime soon after the census in 2010, blacks in Richmond were no longer the majority of population, despite blacks making up over 57 percent of the city’s population as recently as 2000.

A number of other cities in the United States have also seen the black portion of their population slip below 50 percent in recent years. St. Louis’s black population declined below 50 percent during the late 2000s as many of its black residents moved out to suburbs such as Ferguson. When the 2010 census showed that blacks no longer made up the majority of Washington D.C’s population, the change received a good deal of attention in the media.

Though the recent transformation of Richmond has been hard to miss, it has not received nearly the amount of publicity for several reasons. The black proportion of Washington’s population declined, in part, because other groups moved into the city but also because 40,000 black residents moved out of the city, many of whom felt they no longer could afford to live in it. In contrast, Richmond’s black population actually grew but its portion of the total population shrunk due to other groups growing much faster.

Richmond’s black population is not growing as quickly as the total population in large part because blacks in the Richmond metro area remain disproportionately concentrated within the city as a legacy of segregation. Now the concentration of blacks is beginning to lessen; in 2000, 13 census tracts in Richmond were over 95 percent black, but by 2013 only 4 of these census tracts were still over 95 percent black. During this same time period, the black population in the Richmond metro area’s suburban counties grew quickly as many of the city’s black residents moved to them.

On the longer term, it is unlikely that the city will return to having either a black or white majority. Though Richmond’s black population has grown slowly in recent years, the number of people living in Richmond who describe themselves as being more than one race has tripled since 2000 to a little under 9,000. This is likely in part due to Virginia having the highest rate of marriage between blacks and whites in the country, but also because as racial identity means increasingly less today, many people are identifying with more than one race, some even writing in their own race. Considering how much publicity the last major demographic change in Richmond received, the lack of attention given to the current one reveals how much Richmond itself has changed.